The natural world resonates with an extraordinary diversity of sounds, from the melodious songs of birds to the mysterious clicks of marine mammals. Understanding animal vocalizations reveals intricate communication systems that rival human language in complexity.

🎵 The Universal Language of Nature

Animal sounds represent one of the most fascinating aspects of biological communication. Every chirp, click, song, and alarm carries specific meaning within its ecological context. These vocalizations serve essential functions: attracting mates, defending territories, warning of predators, coordinating group movements, and maintaining social bonds. The taxonomy of animal sounds provides scientists with a framework for understanding how different species have evolved distinct acoustic signatures suited to their environments and social structures.

Researchers in bioacoustics have dedicated decades to cataloging and analyzing these sounds, revealing patterns that connect evolutionary history, habitat requirements, and behavioral ecology. The complexity of animal communication challenges our anthropocentric view of language and intelligence, demonstrating that sophisticated information exchange exists throughout the animal kingdom.

Chirps: The Rhythmic Pulses of Small Creatures

Chirping represents one of the most recognizable categories of animal vocalizations, predominantly associated with insects, small birds, and certain rodents. These brief, repetitive sounds typically serve territorial or reproductive functions, with each species possessing a unique acoustic fingerprint.

The Cricket’s Mathematical Precision 🦗

Crickets produce their characteristic chirps through stridulation, rubbing specialized wing structures together at remarkable speeds. The rate of chirping correlates directly with ambient temperature, following predictable mathematical relationships. Male crickets adjust their chirp patterns to advertise their fitness to potential mates, with faster, more consistent chirping indicating superior genetic quality.

Different cricket species produce distinct chirp patterns, allowing them to avoid costly mating mistakes with incompatible species. The field cricket generates continuous trills, while the tree cricket produces more spaced, melodious notes. This acoustic diversity enables multiple species to coexist in the same habitat without signal interference.

Avian Chirps and Contact Calls

Many small songbirds use short chirps as contact calls, maintaining flock cohesion while foraging or during migration. These simple vocalizations differ dramatically from elaborate songs, serving immediate practical needs rather than long-term reproductive strategies. Sparrows, finches, and warblers constantly exchange chirps that convey location, activity status, and mild alarm signals.

Research demonstrates that birds can recognize individual companions through subtle variations in chirp structure, suggesting these brief sounds contain more information than initially apparent. Young birds learn appropriate chirping patterns from their parents and flock mates, indicating cultural transmission of acoustic behavior.

Clicks: Precision Instruments of Echolocation and Communication

Clicking sounds represent some of the most sophisticated acoustic signals in nature, particularly among marine mammals and certain terrestrial species. These brief, broadband pulses serve dual purposes: navigation through echolocation and complex social communication.

Dolphin Dialects and Signature Whistles 🐬

Dolphins produce various click patterns for echolocation, generating rapid sequences that bounce off objects and return detailed environmental information. These biosonar clicks operate at frequencies between 40 and 130 kHz, far beyond human hearing range. The returning echoes allow dolphins to distinguish between different fish species, determine object size and texture, and navigate murky waters with extraordinary precision.

Beyond echolocation, dolphins use clicks for social communication, often combined with whistles and burst-pulse sounds. Each dolphin develops a signature whistle—essentially a unique name—that others use to call specific individuals. This naming behavior suggests abstract thinking and individual recognition comparable to human social cognition.

Sperm Whales and Codas

Sperm whales produce the loudest biological sounds on Earth, with clicks reaching 230 decibels. These magnificent cetaceans organize their clicks into rhythmic patterns called codas, which function as cultural markers distinguishing different whale clans. Researchers have identified distinct vocal dialects associated with specific social groups, passed down through generations.

The complexity of sperm whale communication suggests sophisticated cognitive abilities. Different coda patterns correlate with specific social contexts: greeting sequences, coordinated diving preparations, and mother-calf bonding interactions. This structured communication system indicates rule-based syntax similar to human language fundamentals.

Songs: The Elaborate Compositions of Courtship and Territory

Among all animal vocalizations, songs represent the most complex and culturally rich category. These extended, structured sequences combine multiple note types into coherent patterns that convey extensive information about the singer’s identity, quality, and intentions.

The Virtuoso Performances of Songbirds 🎶

Songbird vocalizations exhibit remarkable sophistication, with some species possessing repertoires exceeding 2,000 distinct song types. The brown thrasher, nightingale, and mockingbird demonstrate extraordinary vocal learning abilities, memorizing and reproducing sounds from their environment, including other bird species and even mechanical noises.

Male songbirds typically produce elaborate songs during breeding seasons to attract females and defend territories. Song complexity, consistency, and endurance serve as honest signals of male quality, as only healthy birds with superior cognitive abilities can master and perform demanding vocal repertoires. Females assess these performances carefully, selecting mates based on song characteristics that indicate good genes and parenting potential.

Neural Architecture of Birdsong

The neurological basis of birdsong has provided crucial insights into learning and memory. Birds possess specialized brain regions dedicated to song production and learning, including the HVC (used as a proper name) and robust nucleus of the arcopallium. These neural circuits show remarkable plasticity during critical learning periods when young birds memorize tutor songs.

Seasonal changes affect song-control brain regions, with volumes increasing during breeding seasons when singing intensifies. This neuroplasticity demonstrates how brain structure adapts to behavioral demands, offering parallels to human language acquisition and maintenance.

Marine Mammal Symphonies

Humpback whales produce perhaps the most hauntingly beautiful songs in nature, with compositions lasting 10-20 minutes and repeated for hours. All males within a population sing the same song, which gradually evolves throughout the breeding season. These coordinated changes suggest cultural transmission and conformity, with new phrases spreading through populations like musical trends.

The function of humpback whale songs remains partially mysterious. While clearly associated with breeding, whether they primarily attract females, establish male dominance hierarchies, or serve other purposes continues to generate scientific debate. The songs’ complexity and constant evolution suggest multiple overlapping functions within whale social dynamics.

Alarm Calls: The Language of Survival 🚨

Alarm vocalizations represent critical survival adaptations, enabling animals to warn conspecifics about predators and other threats. These sounds often display remarkable specificity, with different calls corresponding to distinct danger types, predator locations, and urgency levels.

The Sophisticated Warning Systems of Primates

Vervet monkeys possess one of the best-studied alarm call systems, producing acoustically distinct vocalizations for different predators. Leopard alarms trigger climbing behavior, eagle alarms cause vervets to look upward and seek cover, and snake alarms prompt standing upright and scanning the ground. This referential communication demonstrates that alarm calls function as symbolic representations of specific threats rather than mere emotional expressions.

Young vervets must learn appropriate responses to these alarm calls, sometimes making costly mistakes before mastering the system. This learning process reveals that primate vocalizations, though partially innate, require social experience for full functionality—another parallel with human language development.

Prairie Dog Vocabulary

Prairie dogs demonstrate astonishing specificity in their alarm calls, with vocalizations encoding information about predator type, size, color, and approach speed. Researcher Con Slobodchikoff discovered that prairie dogs produce different calls for humans wearing different colored shirts, suggesting their communication system approaches descriptive language.

These complex alarm systems challenge traditional distinctions between human language and animal communication. The prairie dog example demonstrates that non-human animals can convey detailed, specific information about external objects—a capability once considered uniquely human.

Avian Sentinel Behavior

Many bird species employ sentinel systems where individuals take turns watching for predators while others forage. Sentinels produce specific alarm calls that communicate threat type and urgency. Chickadees, for instance, use a graded alarm system where more “dee” notes indicate smaller, more maneuverable predators requiring different evasive strategies.

These alarm systems benefit the entire group, raising questions about altruism and cooperation. Sentinels risk attracting predator attention by calling, yet this behavior persists because mutual vigilance increases everyone’s survival probability, including kin who share the sentinel’s genes.

Cross-Modal Communication and Multimodal Signals

Animal communication rarely relies on sound alone. Many species combine vocalizations with visual displays, chemical signals, and tactile cues to create multimodal messages that enhance information transmission and reduce ambiguity.

The Dance Language of Honeybees

While honeybees communicate primarily through dance—a visual-tactile modality—they also produce specific sounds during waggle dances. These vibrations provide additional information about food source quality and distance, demonstrating how animals integrate multiple sensory channels for maximum communicative efficiency.

Frog Choruses and Visual Displays

Male frogs combine vocal advertisement with inflated vocal sacs that serve as visual signals. The combination of sound and sight helps females locate callers in dense vegetation and assess male quality through both acoustic and visual cues. Some species add foot-flagging behaviors in noisy environments where acoustic signals become degraded.

Technology Transforming Animal Communication Research 📱

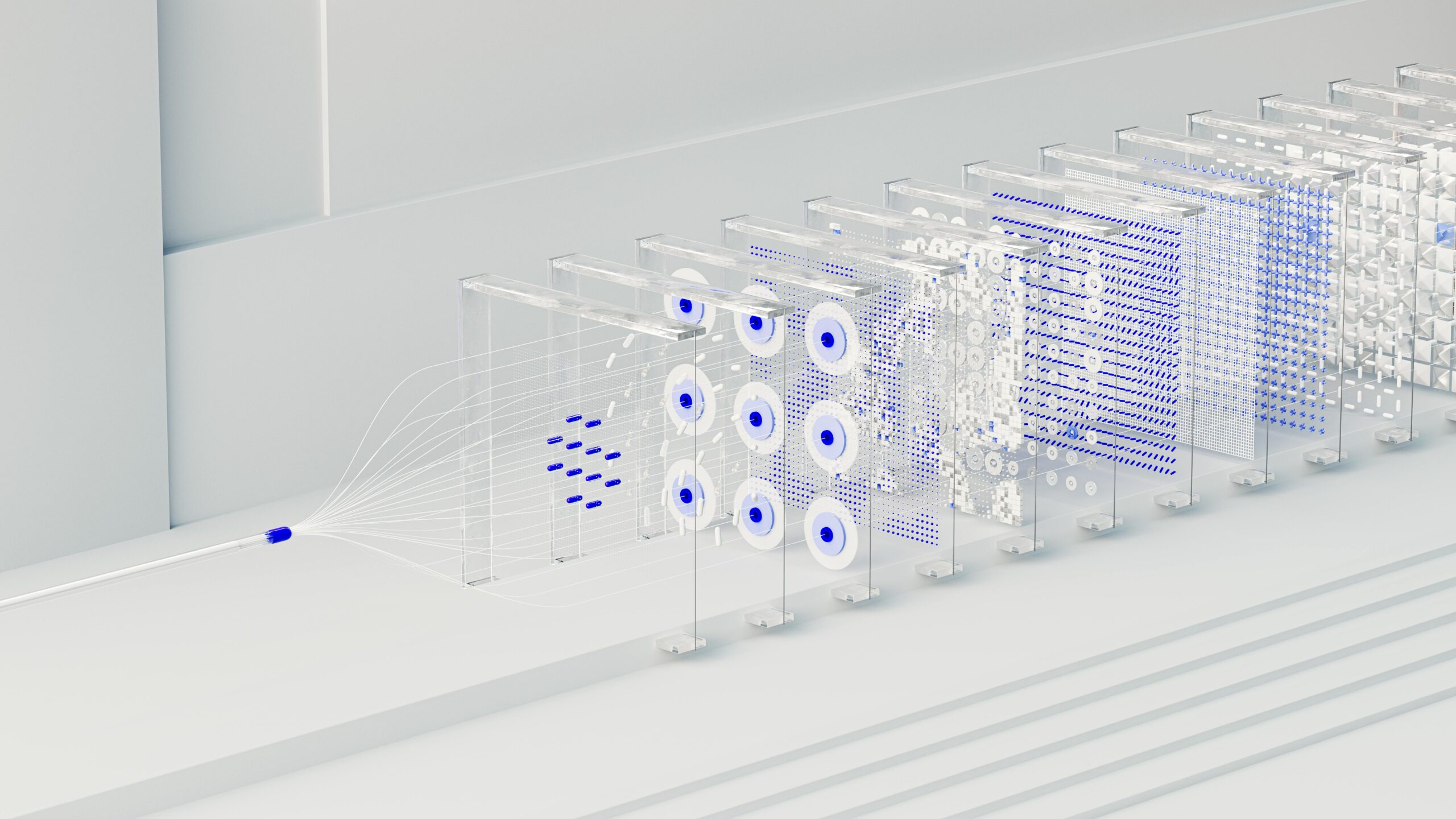

Modern technology has revolutionized our ability to record, analyze, and interpret animal vocalizations. Sophisticated recording equipment, machine learning algorithms, and acoustic analysis software enable researchers to detect patterns invisible to human perception.

Bioacoustic Monitoring and Conservation

Passive acoustic monitoring deploys autonomous recording devices in habitats to continuously capture soundscapes. These recordings help scientists track population changes, identify rare species, and assess ecosystem health through acoustic diversity indices. Conservation efforts increasingly incorporate bioacoustic data to make informed management decisions.

Machine learning algorithms now automatically classify animal vocalizations from massive datasets, identifying individual animals, detecting rare species, and monitoring behavioral changes across seasons. This computational approach enables large-scale studies previously impossible due to the time required for manual analysis.

Evolutionary Perspectives on Vocal Communication

Understanding the taxonomy of animal sounds requires evolutionary context. Vocalizations reflect adaptations to specific ecological niches, with sound characteristics shaped by habitat acoustics, predation pressure, and social structure.

Acoustic Adaptation Hypothesis

Bird songs vary predictably across habitats, with forest species producing lower-frequency, slower songs that propagate better through dense vegetation, while open-habitat species use higher frequencies and faster tempos. This acoustic adaptation optimizes signal transmission given environmental constraints, demonstrating how physics shapes biological evolution.

The Evolutionary Arms Race

Predator-prey relationships drive vocal evolution. Some prey species evolve alarm calls with acoustic properties that make localization difficult for predators, while predators develop hearing sensitivities tuned to prey vocalizations. This coevolutionary dynamic constantly reshapes the acoustic landscape.

The Future Symphony: Climate Change and Shifting Soundscapes 🌍

Anthropogenic environmental changes profoundly affect animal communication systems. Climate change alters breeding phenologies, potentially disrupting the timing of vocal displays relative to optimal conditions. Ocean acidification affects sound propagation underwater, potentially degrading marine mammal communication over long distances.

Noise pollution from human activities masks animal vocalizations, forcing some species to alter their calling times, frequencies, or amplitudes. Urban birds sing at higher pitches and increased volumes compared to rural counterparts, demonstrating rapid adaptation to anthropogenic soundscapes. However, these adaptations may carry fitness costs, reducing communication efficiency and breeding success.

Habitat fragmentation isolates populations, reducing opportunities for vocal learning and cultural transmission. Small, isolated populations may lose vocal diversity over generations, potentially affecting mate recognition and species cohesion. Conservation efforts must consider these acoustic dimensions alongside traditional habitat and genetic management.

Listening to the Living Planet

The symphony of animal sounds represents far more than pleasant background noise in natural settings. Each chirp, click, song, and alarm contributes to complex communication networks that maintain ecological relationships, coordinate social behaviors, and ensure species survival. By decoding these acoustic taxonomies, we gain profound insights into animal cognition, evolution, and the intricate web of life.

Understanding animal vocalizations also deepens our connection to the natural world, revealing the rich subjective experiences of non-human species. As we face unprecedented environmental challenges, listening to and protecting these diverse voices becomes increasingly urgent. The acoustic diversity surrounding us reflects the biological diversity that sustains planetary health and enriches human existence.

Future research will continue unveiling new complexities in animal communication, challenging our assumptions about intelligence, consciousness, and the boundaries between human and non-human capacities. The more carefully we listen, the more we discover that we share this planet with remarkably sophisticated communicators whose voices deserve our attention, respect, and protection. Their songs, clicks, chirps, and alarms compose an irreplaceable natural heritage—a living library of evolutionary wisdom written in sound across millions of years.

Toni Santos is a bioacoustic researcher and conservation technologist specializing in the study of animal communication systems, acoustic monitoring infrastructures, and the sonic landscapes embedded in natural ecosystems. Through an interdisciplinary and sensor-focused lens, Toni investigates how wildlife encodes behavior, territory, and survival into the acoustic world — across species, habitats, and conservation challenges. His work is grounded in a fascination with animals not only as lifeforms, but as carriers of acoustic meaning. From endangered vocalizations to soundscape ecology and bioacoustic signal patterns, Toni uncovers the technological and analytical tools through which researchers preserve their understanding of the acoustic unknown. With a background in applied bioacoustics and conservation monitoring, Toni blends signal analysis with field-based research to reveal how sounds are used to track presence, monitor populations, and decode ecological knowledge. As the creative mind behind Nuvtrox, Toni curates indexed communication datasets, sensor-based monitoring studies, and acoustic interpretations that revive the deep ecological ties between fauna, soundscapes, and conservation science. His work is a tribute to: The archived vocal diversity of Animal Communication Indexing The tracked movements of Applied Bioacoustics Tracking The ecological richness of Conservation Soundscapes The layered detection networks of Sensor-based Monitoring Whether you're a bioacoustic analyst, conservation researcher, or curious explorer of acoustic ecology, Toni invites you to explore the hidden signals of wildlife communication — one call, one sensor, one soundscape at a time.