The ocean conceals vast populations of marine life, and scientists continuously develop innovative methods to estimate their numbers without disrupting delicate ecosystems.

🌊 The Challenge of Counting in the Deep Blue

Imagine trying to count every fish in a swimming pool while blindfolded. Now multiply that challenge by millions and extend it across thousands of miles of ocean. This is the reality marine biologists face when attempting to estimate species abundance in our oceans. Traditional visual surveys have significant limitations—murky water, vast distances, and the simple fact that most marine animals don’t conveniently line up to be counted.

Enter acoustic technology, a revolutionary approach that uses sound waves to detect and estimate marine populations. This method has transformed our understanding of ocean ecosystems, particularly for species that produce distinctive sounds or have specific acoustic signatures. From whales singing their haunting songs to fish schools reflecting sonar beams, acoustic encounter rates offer a window into underwater abundance that was previously impossible to achieve.

Understanding Acoustic Encounter Rates: The Foundation

Acoustic encounter rates represent the frequency at which researchers detect animal sounds or echoes within a specific time period and geographic area. This metric serves as a proxy for population density, allowing scientists to estimate how many individuals occupy a given region without physically seeing or capturing them.

The principle is elegantly simple: deploy underwater microphones called hydrophones or use active sonar systems, then count how often you encounter acoustic signals from your target species. The more encounters per unit time or distance traveled, the higher the presumed abundance. However, translating these encounters into actual population numbers requires sophisticated mathematical models and careful calibration.

The Two Primary Acoustic Approaches

Passive acoustic monitoring relies on listening to sounds that animals naturally produce. Marine mammals, particularly cetaceans, are ideal candidates for this method. Their vocalizations—whether echolocation clicks, social calls, or breeding songs—create distinctive acoustic signatures that researchers can identify and count.

Active acoustic surveys, conversely, involve transmitting sound waves and analyzing the echoes that bounce back from animals or objects. This technique, commonly called echosounder or sonar surveying, works exceptionally well for fish schools and zooplankton aggregations that reflect sound differently than surrounding water.

🔬 The Science Behind Sound in Water

Sound travels differently through water than air—approximately 4.3 times faster, in fact. This property makes acoustic methods particularly effective in marine environments. Water’s density allows sound waves to propagate over vast distances with relatively little energy loss, enabling researchers to detect animals kilometers away from their recording equipment.

Different frequencies penetrate water at varying depths and distances. Low-frequency sounds travel farther but provide less detailed information, while high-frequency sounds offer precision at shorter ranges. Scientists must carefully select their equipment frequencies based on target species, water depth, and survey objectives.

Environmental factors significantly influence acoustic propagation. Temperature layers, salinity gradients, and seafloor composition all affect how sound travels underwater. Sophisticated models account for these variables, ensuring accurate interpretation of acoustic data. Background noise from shipping traffic, weather, and geological activity adds complexity, requiring advanced filtering techniques to isolate biological signals.

From Encounters to Estimates: The Mathematical Journey

Converting raw acoustic encounters into population estimates involves several critical steps. First, researchers must establish detection probability—the likelihood that an animal within the survey area will actually be detected. Not every animal vocalizes constantly, and equipment has physical detection limits based on range and sensitivity.

The effective detection area forms another crucial parameter. This represents the zone within which the acoustic equipment can reliably detect target animals. For passive systems, this depends on vocalization strength and frequency. For active systems, it relates to sound beam geometry and target acoustic properties.

Key Calculation Components

Population density estimation typically follows this framework:

- Calculate encounter rate: number of acoustic detections per unit effort (time or distance)

- Determine effective detection radius or area based on equipment specifications and environmental conditions

- Estimate vocalization or availability bias—the proportion of time animals are acoustically available

- Apply correction factors for missed detections and false positives

- Scale up from sampled area to total survey region

Statistical models provide confidence intervals around these estimates, acknowledging inherent uncertainties. Bayesian approaches increasingly incorporate prior knowledge and multiple data sources, producing more robust abundance estimates with quantified uncertainty.

🐋 Success Stories: Whales, Dolphins, and Beyond

Acoustic encounter rates have revolutionized cetacean research. Baleen whales produce low-frequency calls detectable across ocean basins, enabling large-scale abundance surveys impossible through visual methods alone. Blue whale populations off California, fin whales in the North Atlantic, and right whales near shipping lanes have all been assessed using acoustic techniques.

Sperm whales present an ideal case study. Their distinctive echolocation clicks, produced during deep foraging dives, provide consistent acoustic cues. Researchers have developed standardized methods to estimate sperm whale density from click encounter rates, accounting for dive behavior and group size. These methods now support population assessments across global oceans, informing conservation management decisions.

Dolphin species with signature whistles offer another success story. By cataloging individual vocal signatures, scientists can both estimate population size and track specific animals over time. This combination of abundance estimation and individual identification provides unprecedented insights into population dynamics, social structure, and habitat use patterns.

Beyond Marine Mammals

Fish populations increasingly benefit from acoustic abundance estimates. Schooling species like herring, anchovy, and pollock reflect sonar signals distinctively, allowing fisheries managers to assess stock sizes before setting catch quotas. Multi-frequency systems can even differentiate between species based on their acoustic properties, enabling simultaneous surveys of multiple commercial species.

Invertebrates aren’t left out either. Snapping shrimp, despite their small size, produce loud popping sounds that dominate many coastal soundscapes. Their acoustic activity correlates with population density, offering a novel way to monitor these ecologically important crustaceans. Even squid, traditionally difficult to survey, can be detected acoustically based on their unique backscatter properties.

⚙️ Technology Evolution: From Analog to AI

Early acoustic surveys relied on analog recording equipment and manual analysis—researchers literally listening to hours of recordings and counting sounds by hand. This labor-intensive process limited survey scope and temporal coverage.

Digital recording revolutionized the field, enabling continuous long-term deployments. Modern autonomous recorders can operate for months, capturing terabytes of acoustic data across seasonal cycles. This temporal richness reveals patterns impossible to detect through snapshot surveys—migration timing, breeding season duration, and responses to environmental changes.

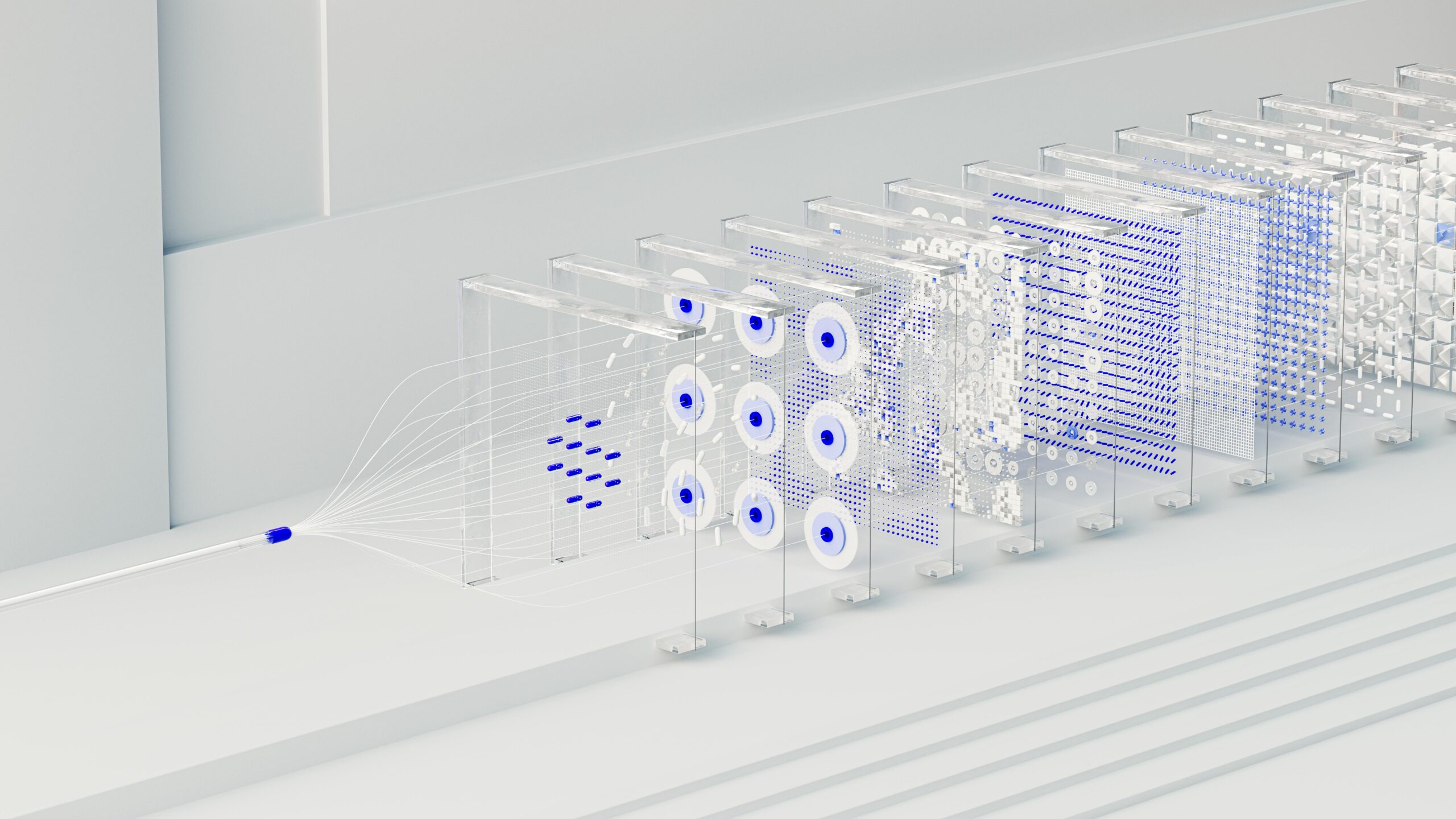

Artificial intelligence now automates detection and classification tasks that once required expert human analysts. Machine learning algorithms trained on thousands of labeled examples can identify species-specific calls with accuracy rivaling or exceeding human performance. Deep neural networks process acoustic spectrograms like images, recognizing patterns across time and frequency dimensions.

Real-Time Monitoring Systems

Cutting-edge systems transmit acoustic data in real-time via satellite or cellular networks. These platforms enable dynamic management responses—shipping lane adjustments when whales are detected, fishing closure enforcement when spawning aggregations form, or immediate alerts for unusual mortality events. The transition from retrospective analysis to real-time awareness marks a paradigm shift in marine conservation.

Integrated systems combine acoustic sensors with environmental measurements—temperature, salinity, chlorophyll, and currents. These multivariate datasets reveal relationships between animal abundance and habitat characteristics, supporting predictive models of species distribution. Such ecosystem-based approaches inform marine spatial planning and climate change adaptation strategies.

📊 Challenges and Limitations: Navigating Uncertainty

Despite impressive capabilities, acoustic methods face significant challenges. Species identification can be problematic when multiple species produce similar sounds or when vocalizations vary across regions and contexts. Acoustic taxonomies remain incomplete for many groups, particularly fish species with poorly documented sound production.

Behavioral variability complicates abundance estimation. Animals don’t vocalize constantly or predictably. Feeding, socializing, resting, and traveling may involve different acoustic activity levels. Seasonal patterns, diel rhythms, and responses to environmental conditions all influence detection probability. Models must account for this variation or risk biased estimates.

The fundamental assumption—that acoustic encounter rates correlate with actual abundance—requires validation. Ground-truthing through independent survey methods (visual surveys, tagging studies, or fisheries catches) remains essential but logistically challenging. Calibration efforts are resource-intensive and often species-specific, limiting method transferability.

Technical and Environmental Constraints

Equipment costs restrict survey coverage. While prices have declined, comprehensive acoustic monitoring networks remain expensive to establish and maintain. Battery life, data storage capacity, and biofouling all limit autonomous recorder deployments, particularly in remote locations.

Anthropogenic noise pollution increasingly compromises acoustic surveys. Shipping, construction, seismic exploration, and military activities mask biological sounds, reducing detection ranges and increasing false negative rates. Climate change-driven environmental shifts may alter sound propagation characteristics, requiring ongoing recalibration of detection models.

🌍 Global Applications: Conservation and Management

Acoustic abundance estimates directly inform marine protected area design. By identifying critical habitats with high species density, managers can prioritize conservation efforts where they’ll have maximum impact. Temporal patterns revealed through continuous monitoring help define seasonal closures that protect animals during vulnerable life stages.

Fisheries management increasingly incorporates acoustic stock assessments. Traditional methods like trawl surveys harm target species and bycatch while sampling only small areas. Acoustic surveys offer non-invasive alternatives covering larger regions with reduced ecological footprint. Integration with ecosystem models supports sustainable harvest strategies balancing economic and conservation objectives.

Shipping industry collaboration leverages acoustic technology to reduce vessel strikes. Real-time whale detection systems alert ships to slow down or alter course when animals are nearby. These systems have demonstrably reduced collision mortality in high-risk areas, proving that technology can mediate human-wildlife conflicts.

Climate Change Monitoring

Long-term acoustic datasets document species responses to ocean warming, acidification, and deoxygenation. Distributional shifts, phenological changes, and community composition alterations all leave acoustic signatures. These baselines enable detection of significant ecological changes before they become irreversible, supporting adaptive management under uncertain futures.

Biodiversity monitoring programs deploy standardized acoustic methods across global networks. Comparable data from diverse ecosystems reveal large-scale patterns and trends impossible to discern from isolated studies. This coordination advances marine ecology from case studies toward predictive science capable of forecasting ecosystem trajectories.

🔮 Future Horizons: What’s Next for Acoustic Science

Miniaturization and cost reduction will democratize acoustic monitoring. Citizen science initiatives may soon equip recreational boaters, divers, and coastal residents with affordable sensors, vastly expanding survey coverage. Crowdsourced acoustic data, properly curated and analyzed, could revolutionize our understanding of coastal ecosystem dynamics.

Integration with other remote sensing platforms promises holistic ecosystem assessment. Satellite-derived ocean color, temperature, and altimetry combined with acoustic abundance estimates will enable comprehensive biodiversity mapping. Autonomous underwater vehicles carrying acoustic sensors will access previously unreachable habitats—ice-covered regions, deep trenches, and remote seamounts.

Advanced analytics will extract more information from existing datasets. Individual identification from acoustic signatures may become routine, enabling mark-recapture studies without physical tags. Social network analysis of group calling patterns could reveal population structure and connectivity. Bioacoustic big data holds secrets we’re only beginning to unlock.

💡 Practical Implementation: Getting Started

Organizations or researchers interested in acoustic abundance surveys should begin with clear objectives. What species are priorities? What spatial and temporal scales matter for management decisions? These questions guide equipment selection, deployment strategies, and analytical approaches.

Collaboration accelerates progress. Established networks offer expertise, standardized protocols, and data-sharing platforms. Training programs build capacity in acoustic analysis techniques. Open-source software reduces barriers to entry, making sophisticated analysis accessible beyond well-funded institutions.

Pilot studies validate methods before major investments. Small-scale deployments test equipment performance, refine detection algorithms, and calibrate abundance models against independent data. Iterative improvement based on lessons learned ensures resources support robust, defensible estimates rather than generating questionable numbers.

🎯 Bridging Science and Action

The true value of acoustic abundance estimates emerges when they inform decisions that benefit marine ecosystems. Scientists must communicate findings effectively to managers, policymakers, and public audiences. Visualizations, story-telling, and accessible language transform technical results into compelling calls for conservation action.

Stakeholder engagement ensures research addresses real-world needs. Fishing communities, tourism operators, indigenous groups, and conservation organizations all hold valuable knowledge and perspectives. Co-production of research questions and interpretation of findings builds trust and increases implementation likelihood.

Adaptive management frameworks incorporate acoustic monitoring as feedback mechanisms. Regular abundance assessments reveal whether management actions achieve intended outcomes. This evidence-based approach allows course corrections, optimizing strategies over time as understanding improves and conditions change.

The ocean’s acoustic realm offers extraordinary opportunities to understand and protect marine biodiversity. As technology advances and methods mature, acoustic encounter rates will increasingly guide evidence-based ocean stewardship. From the songs of whales to the echoes of fish schools, sounds beneath the waves tell stories of abundance, distribution, and ecosystem health. By learning to listen and interpret these acoustic narratives, we unlock secrets essential for ensuring ocean vitality for generations to come.

Toni Santos is a bioacoustic researcher and conservation technologist specializing in the study of animal communication systems, acoustic monitoring infrastructures, and the sonic landscapes embedded in natural ecosystems. Through an interdisciplinary and sensor-focused lens, Toni investigates how wildlife encodes behavior, territory, and survival into the acoustic world — across species, habitats, and conservation challenges. His work is grounded in a fascination with animals not only as lifeforms, but as carriers of acoustic meaning. From endangered vocalizations to soundscape ecology and bioacoustic signal patterns, Toni uncovers the technological and analytical tools through which researchers preserve their understanding of the acoustic unknown. With a background in applied bioacoustics and conservation monitoring, Toni blends signal analysis with field-based research to reveal how sounds are used to track presence, monitor populations, and decode ecological knowledge. As the creative mind behind Nuvtrox, Toni curates indexed communication datasets, sensor-based monitoring studies, and acoustic interpretations that revive the deep ecological ties between fauna, soundscapes, and conservation science. His work is a tribute to: The archived vocal diversity of Animal Communication Indexing The tracked movements of Applied Bioacoustics Tracking The ecological richness of Conservation Soundscapes The layered detection networks of Sensor-based Monitoring Whether you're a bioacoustic analyst, conservation researcher, or curious explorer of acoustic ecology, Toni invites you to explore the hidden signals of wildlife communication — one call, one sensor, one soundscape at a time.