Acoustic monitoring has emerged as a revolutionary approach to understanding and protecting biodiversity, offering scientists and conservationists powerful tools to assess ecosystem health remotely.

🎵 The Soundscape Revolution in Conservation Biology

In the dense rainforests of the Amazon, the high-altitude meadows of the Himalayas, and the coral reefs of the Pacific, a silent revolution is taking place. Scientists are no longer just observing wildlife with their eyes—they’re listening with unprecedented precision. Acoustic indices have transformed how we monitor, understand, and protect the natural world, providing quantitative measures that capture the complexity of biological soundscapes in ways traditional methods never could.

The concept of soundscape ecology emerged in the late 20th century, but only in recent decades have computational advances made it possible to analyze vast amounts of acoustic data efficiently. Today, acoustic indices serve as vital biomarkers, offering insights into species diversity, ecosystem health, habitat quality, and environmental changes with remarkable speed and accuracy.

Understanding Acoustic Indices: The Foundation

Acoustic indices are mathematical algorithms designed to summarize acoustic complexity and patterns in recorded soundscapes. Unlike traditional biodiversity surveys that require extensive field time and taxonomic expertise, these indices can process hours of recordings in minutes, extracting meaningful ecological information from the symphony of natural sounds.

These tools work by analyzing various acoustic properties including frequency distribution, amplitude variation, temporal patterns, and signal complexity. Each index captures different aspects of the soundscape, and when used together, they provide a comprehensive picture of ecosystem dynamics.

The Science Behind Sound Measurement

Sound in nature carries information across multiple dimensions. Frequency tells us which species might be present—birds typically vocalize at higher frequencies than frogs or mammals. Amplitude reveals how loud the environment is, which can indicate biological activity levels. Temporal patterns show when different species are active, revealing circadian rhythms and seasonal variations.

Acoustic indices mathematically quantify these properties, transforming raw sound into actionable ecological data. This transformation enables large-scale monitoring projects that would be impossible using conventional survey methods alone.

🔍 Essential Acoustic Indices Every Conservationist Should Know

Acoustic Complexity Index (ACI)

The Acoustic Complexity Index measures the variability of sound intensity across frequencies and time. Developed specifically for bird vocalizations, ACI has proven valuable across diverse taxa. It works on the principle that biotic sounds exhibit more intensity modulation than abiotic sounds like wind or rain.

In practical conservation applications, ACI has successfully tracked habitat restoration progress, detected invasive species impacts, and monitored seasonal biodiversity changes. Studies in temperate forests have shown strong correlations between ACI values and traditional bird species counts, validating its effectiveness as a biodiversity proxy.

Acoustic Diversity Index (ADI)

The Acoustic Diversity Index calculates the diversity of sounds across frequency bands using the Shannon diversity formula. By dividing the acoustic spectrum into bins and measuring the evenness of sound energy distribution, ADI provides insights into acoustic niche occupancy.

Conservation projects in tropical rainforests have used ADI to identify biodiversity hotspots and track ecosystem recovery after disturbance. Higher ADI values typically indicate greater acoustic diversity, suggesting more complex biological communities with multiple species utilizing different acoustic niches.

Bioacoustic Index (BI)

Specifically designed to focus on frequency ranges where biological sounds predominate, the Bioacoustic Index filters out low-frequency anthropogenic noise. It calculates the area under the sound spectrum curve between 2 kHz and 8 kHz, where most bird and insect vocalizations occur.

BI has proven particularly useful in human-modified landscapes where distinguishing biological from anthropogenic sounds is crucial. Urban ecology studies employ BI to assess how wildlife communities adapt to cities and identify green spaces that maintain high biological activity despite urbanization pressures.

Normalized Difference Soundscape Index (NDSI)

The NDSI provides a ratio between anthropogenic and biological sounds by comparing energy in different frequency ranges. Values range from -1 to +1, with positive values indicating biophony dominance and negative values showing anthrophony dominance.

This index excels in environments where human activity is prevalent. Conservation managers use NDSI to evaluate the success of noise mitigation strategies in protected areas, monitor tourism impacts on wildlife, and identify acoustic refugia where biological sounds still dominate despite surrounding development.

Acoustic Evenness Index (AEI)

The Acoustic Evenness Index measures how evenly sound is distributed across frequency bands using the Gini coefficient. Like species evenness in traditional ecology, acoustic evenness reflects community structure and resource partitioning.

Marine conservation projects have successfully applied AEI to reef soundscapes, where crustaceans, fish, and marine mammals create distinct acoustic signatures. Declining AEI values often precede visible ecosystem degradation, making this index valuable for early warning systems.

🌍 Real-World Applications Transforming Conservation

Monitoring Remote and Inaccessible Ecosystems

Acoustic indices shine brightest where traditional surveys fail. In remote Arctic tundra, dense jungle interiors, or deep ocean environments, autonomous recording units can operate for months, capturing soundscapes continuously. Acoustic indices then process these massive datasets, revealing patterns invisible to intermittent human observation.

A groundbreaking study in the Congo Basin deployed acoustic recorders across a gradient from pristine forest to logged areas. Acoustic indices detected biodiversity declines consistent with species loss documented through intensive field surveys, but at a fraction of the cost and time investment.

Tracking Ecosystem Recovery and Restoration Success

Restoration ecology has embraced acoustic indices as objective measures of ecosystem recovery. When degraded habitats are restored, acoustic complexity typically increases as species recolonize. This provides quantifiable targets for restoration success beyond simple vegetation metrics.

In Australian mine rehabilitation projects, acoustic indices tracked the return of bird communities to restored sites. The data showed that acoustic complexity increased progressively over five years, eventually approaching values recorded in reference ecosystems. This information helped managers refine restoration techniques and demonstrate success to stakeholders.

Early Warning Systems for Environmental Change

Perhaps most powerfully, acoustic indices can detect ecosystem stress before traditional indicators show problems. Changes in soundscape patterns often precede visible biodiversity loss, providing crucial early warnings that enable preventive conservation action.

Coral reef monitoring programs now routinely include acoustic sensors alongside visual surveys. Declining acoustic complexity has preceded coral bleaching events by several weeks, allowing managers to implement emergency protocols potentially reducing mortality.

📊 Integrating Multiple Indices for Robust Assessment

No single acoustic index tells the complete story. Conservation best practices involve deploying suites of complementary indices that capture different soundscape dimensions. This multi-index approach provides redundancy and reveals patterns that single metrics might miss.

A comprehensive acoustic monitoring program might combine ACI for temporal variability, ADI for frequency diversity, NDSI for anthropogenic pressure assessment, and AEI for community structure. Together, these indices create a multidimensional acoustic portrait of ecosystem health.

| Acoustic Index | Primary Focus | Best Application | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACI | Intensity modulation | Bird communities | Sensitive to wind noise |

| ADI | Frequency diversity | General biodiversity | Doesn’t distinguish sources |

| BI | Biophony magnitude | Forest ecosystems | Limited frequency range |

| NDSI | Anthrophony vs biophony | Human-modified landscapes | Requires clear frequency separation |

| AEI | Acoustic evenness | Community structure | Less intuitive interpretation |

🛠️ Practical Implementation: From Field to Analysis

Recording Equipment and Deployment Strategies

Successful acoustic monitoring begins with appropriate equipment. Modern autonomous recording units range from budget-friendly options suitable for pilot studies to professional-grade systems for long-term monitoring. Key considerations include battery life, storage capacity, weather resistance, and audio quality.

Deployment strategy significantly impacts data quality and interpretability. Recorder placement should account for target taxa, habitat structure, and potential noise sources. Standardized protocols regarding recorder height, microphone orientation, and sampling schedules enhance data comparability across sites and studies.

Data Processing and Analysis Workflows

Raw acoustic recordings require processing before index calculation. This typically involves noise reduction, temporal segmentation, and quality control to remove corrupted files or extreme weather events. Open-source software packages like R’s soundecology and Python’s scikit-maad have democratized access to acoustic index calculation tools.

Analytical workflows should include statistical validation comparing acoustic indices against ground-truth biodiversity data. This calibration step ensures indices are meaningfully related to conservation targets in specific ecosystems. Machine learning approaches increasingly complement traditional indices, identifying patterns beyond standard metrics.

🚀 Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

Artificial Intelligence and Deep Learning Integration

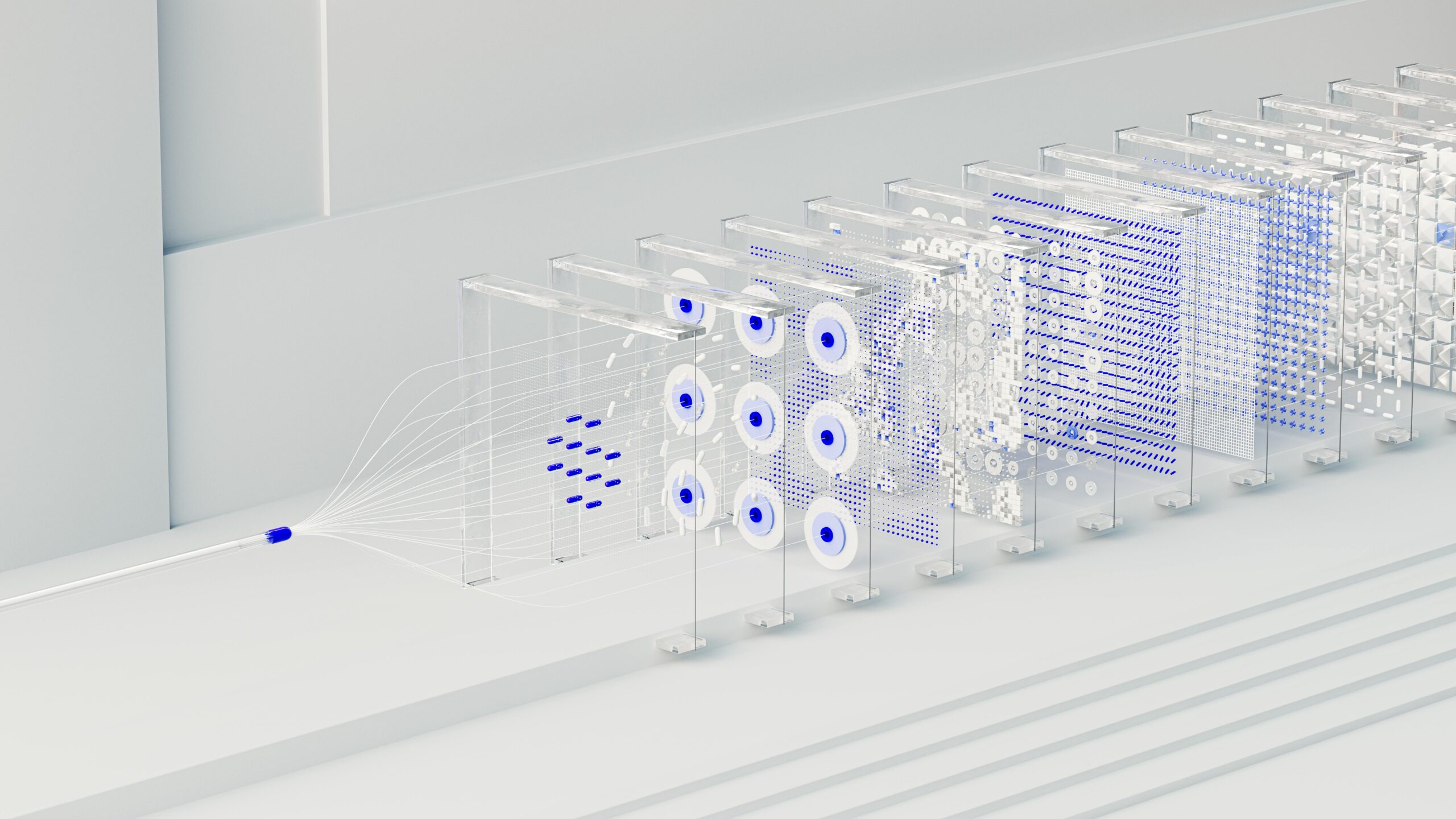

The next generation of acoustic monitoring combines traditional indices with artificial intelligence. Deep learning algorithms now automatically identify individual species from recordings, count vocalizations, and detect rare or cryptic species. When paired with acoustic indices, these AI tools provide both broad ecosystem metrics and fine-scale species information.

Convolutional neural networks trained on vast acoustic libraries can recognize thousands of species with accuracy exceeding human experts. These systems operate continuously, processing data streams in near real-time and flagging anomalies for human review.

Real-Time Monitoring and Adaptive Management

Wireless acoustic sensors now transmit data from field sites to cloud-based analysis platforms in real-time. Conservation managers receive immediate alerts when acoustic indices indicate ecosystem stress, enabling rapid response to threats like illegal logging, poaching, or natural disasters.

This capability transforms conservation from reactive to proactive. Protected area managers can adjust ranger patrols based on acoustic evidence of human encroachment, or modify tourism access when wildlife disturbance exceeds thresholds.

Citizen Science and Community Engagement

Acoustic monitoring creates opportunities for meaningful citizen science participation. Community members can deploy recorders, upload recordings, and contribute to biodiversity documentation without requiring extensive taxonomic training. This democratization of conservation science builds local engagement and generates data at scales impossible for professional researchers alone.

Educational programs teaching acoustic index interpretation empower communities to monitor their own natural resources. Indigenous peoples and local communities possess invaluable ecological knowledge that, combined with acoustic data, creates powerful synergies for conservation effectiveness.

💡 Overcoming Challenges and Limitations

Addressing Methodological Constraints

Despite their power, acoustic indices face legitimate limitations. They cannot identify individual species without additional analysis, may be influenced by non-biological sounds, and require careful interpretation within ecological context. Weather conditions, especially wind and rain, significantly affect recordings and index values.

Addressing these challenges requires transparent reporting of methods, standardized protocols, and integration with complementary monitoring approaches. Acoustic indices should complement rather than replace traditional surveys, creating comprehensive monitoring programs that leverage the strengths of multiple methods.

Building Technical Capacity

Widespread adoption requires building technical capacity across the conservation community. Training programs teaching acoustic monitoring principles, data analysis skills, and result interpretation remain essential. Open-source tools and collaborative networks facilitate knowledge sharing and reduce barriers to entry.

Universities and conservation organizations increasingly offer workshops and online courses covering acoustic monitoring techniques. These educational initiatives ensure acoustic indices reach their full potential as mainstream conservation tools rather than specialized techniques restricted to acoustic ecology experts.

🌟 The Path Forward: Scaling Impact

Acoustic indices represent more than technical innovations—they embody a paradigm shift toward scalable, objective, and cost-effective biodiversity monitoring. As conservation resources remain limited while environmental challenges grow, tools that maximize impact per dollar invested become increasingly critical.

The global community of acoustic ecology researchers continues expanding the acoustic index toolkit, developing new metrics for specific ecosystems and taxa. Standardization efforts aim to create comparable datasets spanning continents and decades, enabling meta-analyses revealing global biodiversity trends.

Success stories multiply as acoustic monitoring proves its value across contexts. From detecting elephant poaching in African savannas to monitoring glacier retreat impacts on alpine ecosystems, acoustic indices reveal conservation insights previously hidden in the soundscape.

🎯 Making Acoustic Indices Work for Your Conservation Goals

For conservation practitioners considering acoustic monitoring implementation, several recommendations ensure success. Start with clear objectives defining what you need to measure and why. Pilot projects testing equipment and protocols in your specific context identify potential challenges before large-scale deployment.

Collaborate with acoustic ecology researchers who can provide methodological guidance and analytical support. Join networks like the International Society of Ecoacoustics connecting practitioners worldwide. Share your data through repositories like the Acoustic Observatory enabling comparative studies and advancing the field collectively.

Most importantly, view acoustic indices as part of an integrated monitoring strategy. Combined with traditional surveys, remote sensing, and local ecological knowledge, acoustic data creates comprehensive understanding supporting effective conservation decision-making.

The power of acoustic indices lies not just in what they measure, but in what they enable—scalable monitoring reaching remote places, objective metrics tracking conservation success, early warnings preventing biodiversity loss, and inclusive approaches engaging communities. As we face unprecedented environmental challenges, these tools offer hope that we can hear, understand, and ultimately protect the natural soundscapes that signify healthy ecosystems.

By unlocking the information encoded in nature’s symphony, acoustic indices transform how we practice conservation. They remind us that protecting biodiversity requires not just seeing, but truly listening to what the natural world tells us. In that listening lies the foundation for conservation success in the decades ahead.

Toni Santos is a bioacoustic researcher and conservation technologist specializing in the study of animal communication systems, acoustic monitoring infrastructures, and the sonic landscapes embedded in natural ecosystems. Through an interdisciplinary and sensor-focused lens, Toni investigates how wildlife encodes behavior, territory, and survival into the acoustic world — across species, habitats, and conservation challenges. His work is grounded in a fascination with animals not only as lifeforms, but as carriers of acoustic meaning. From endangered vocalizations to soundscape ecology and bioacoustic signal patterns, Toni uncovers the technological and analytical tools through which researchers preserve their understanding of the acoustic unknown. With a background in applied bioacoustics and conservation monitoring, Toni blends signal analysis with field-based research to reveal how sounds are used to track presence, monitor populations, and decode ecological knowledge. As the creative mind behind Nuvtrox, Toni curates indexed communication datasets, sensor-based monitoring studies, and acoustic interpretations that revive the deep ecological ties between fauna, soundscapes, and conservation science. His work is a tribute to: The archived vocal diversity of Animal Communication Indexing The tracked movements of Applied Bioacoustics Tracking The ecological richness of Conservation Soundscapes The layered detection networks of Sensor-based Monitoring Whether you're a bioacoustic analyst, conservation researcher, or curious explorer of acoustic ecology, Toni invites you to explore the hidden signals of wildlife communication — one call, one sensor, one soundscape at a time.