Low-power field sensors are revolutionizing environmental monitoring, agriculture, and industrial applications by combining solar energy harvesting with intelligent battery management systems for sustained autonomous operation.

🌞 The Growing Demand for Autonomous Field Sensor Systems

Field sensors deployed in remote locations face a critical challenge: maintaining continuous operation without frequent manual intervention. Whether monitoring soil moisture in vast agricultural fields, tracking wildlife movements in protected reserves, or measuring air quality in urban environments, these devices must function reliably for months or even years without maintenance.

The solution lies in creating self-sustaining power systems that intelligently balance energy harvesting with consumption. Solar panels combined with rechargeable batteries provide the foundation for truly autonomous sensor networks that can operate indefinitely in outdoor environments.

Modern low-power sensors consume remarkably little energy—often just microamperes in sleep mode—making solar and battery combinations not just viable, but highly effective. This technological advancement has opened new possibilities for environmental research, precision agriculture, and infrastructure monitoring at scales previously impossible.

Understanding Power Requirements for Field Sensors

Before designing an effective power solution, you must accurately assess your sensor’s energy demands. Different operational modes consume varying amounts of power, and understanding these patterns is essential for proper system sizing.

📊 Typical Power Consumption Patterns

Most field sensors operate in three distinct modes: sleep, measurement, and transmission. Sleep mode typically consumes 1-50 microamperes, measurement mode requires 5-100 milliamperes for brief periods, and transmission can demand 50-200 milliamperes depending on communication range and protocol.

A soil moisture sensor measuring every hour might spend 99.5% of its time in sleep mode, wake for 10 seconds to take readings, and transmit data for 5 seconds. This duty cycle dramatically reduces average power consumption compared to peak demands.

| Operational Mode | Power Consumption | Typical Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Sleep | 1-10 µA | 99% of time |

| Active Sensing | 20-100 mA | 10-30 seconds/hour |

| Data Transmission | 50-250 mA | 5-20 seconds/hour |

| Solar Charging | Varies with conditions | Daylight hours |

Calculating Daily Energy Budgets

To design an appropriate power system, calculate your daily energy budget in milliampere-hours (mAh) or watt-hours (Wh). Multiply the current consumption of each mode by its duration, then sum all components. Add a safety margin of 30-50% to account for inefficiencies and environmental variations.

For example, a sensor consuming 5 µA in sleep for 23.9 hours, 50 mA for 3 minutes during measurement, and 150 mA for 3 minutes during transmission requires approximately 20 mAh daily at 3.3V—roughly 66 mWh per day.

⚡ Solar Panel Selection and Optimization

Choosing the right solar panel involves balancing size, efficiency, cost, and environmental durability. Modern monocrystalline and polycrystalline panels offer excellent efficiency in compact formats suitable for field deployment.

Panel Sizing Considerations

Solar panel output varies dramatically with location, season, and weather conditions. A panel rated at 1 watt under ideal conditions (1000 W/m² irradiance) might produce only 200-300 mW on a cloudy winter day. Geographic location significantly impacts average daily solar energy availability, measured in peak sun hours.

Equatorial regions receive 4-6 peak sun hours daily year-round, while higher latitudes experience dramatic seasonal variations—from 7-8 hours in summer to 1-2 hours in winter. Your system must sustain operation during the least favorable conditions, not just optimal ones.

For the sensor requiring 66 mWh daily, operating in a location with 3 peak sun hours in winter, you need a panel producing at least 22 mW average power. Accounting for charge controller efficiency (85%), panel degradation, and dirt accumulation, a 100-200 mW rated panel provides adequate margin.

Environmental Durability Features

Field-deployed solar panels must withstand harsh conditions including temperature extremes, humidity, physical impact, and UV exposure. Look for panels with tempered glass surfaces, robust aluminum frames, and IP67 or higher ingress protection ratings.

Encapsulated junction boxes prevent moisture intrusion, while bypass diodes protect against partial shading damage. Quality panels maintain 80% or more of their rated output after 20-25 years, making them exceptionally reliable long-term power sources.

🔋 Battery Technology Choices for Field Applications

Battery selection profoundly impacts system reliability, maintenance requirements, and operational lifespan. Different chemistries offer distinct advantages and limitations for field sensor applications.

Lithium-Ion and LiFePO4 Advantages

Lithium-based batteries dominate modern field sensor applications due to superior energy density, low self-discharge rates, and excellent cycle life. Lithium-ion cells provide 150-250 Wh/kg compared to 30-50 Wh/kg for lead-acid alternatives, enabling smaller, lighter installations.

Lithium Iron Phosphate (LiFePO4) batteries offer exceptional safety, thermal stability, and 2000-5000 charge cycles with minimal capacity degradation. Their flat discharge curve maintains stable voltage throughout discharge, simplifying voltage regulation for sensitive electronics.

Self-discharge rates below 3% monthly mean LiFePO4 batteries retain charge during extended cloudy periods far better than NiMH (20-30% monthly) or lead-acid alternatives. This characteristic proves critical for sensors in regions with seasonal weather patterns.

Capacity Sizing for Reliability

Battery capacity must provide sufficient reserve for several consecutive days without solar charging. The autonomy period depends on application criticality and local weather patterns—typically 3-7 days for most field sensors.

Using our example sensor requiring 66 mWh daily (20 mAh at 3.3V), a 5-day autonomy requirement suggests 100 mAh minimum capacity. However, lithium batteries should not be regularly discharged below 20% capacity to maximize lifespan, effectively requiring 125 mAh usable capacity, or a 500-1000 mAh rated battery.

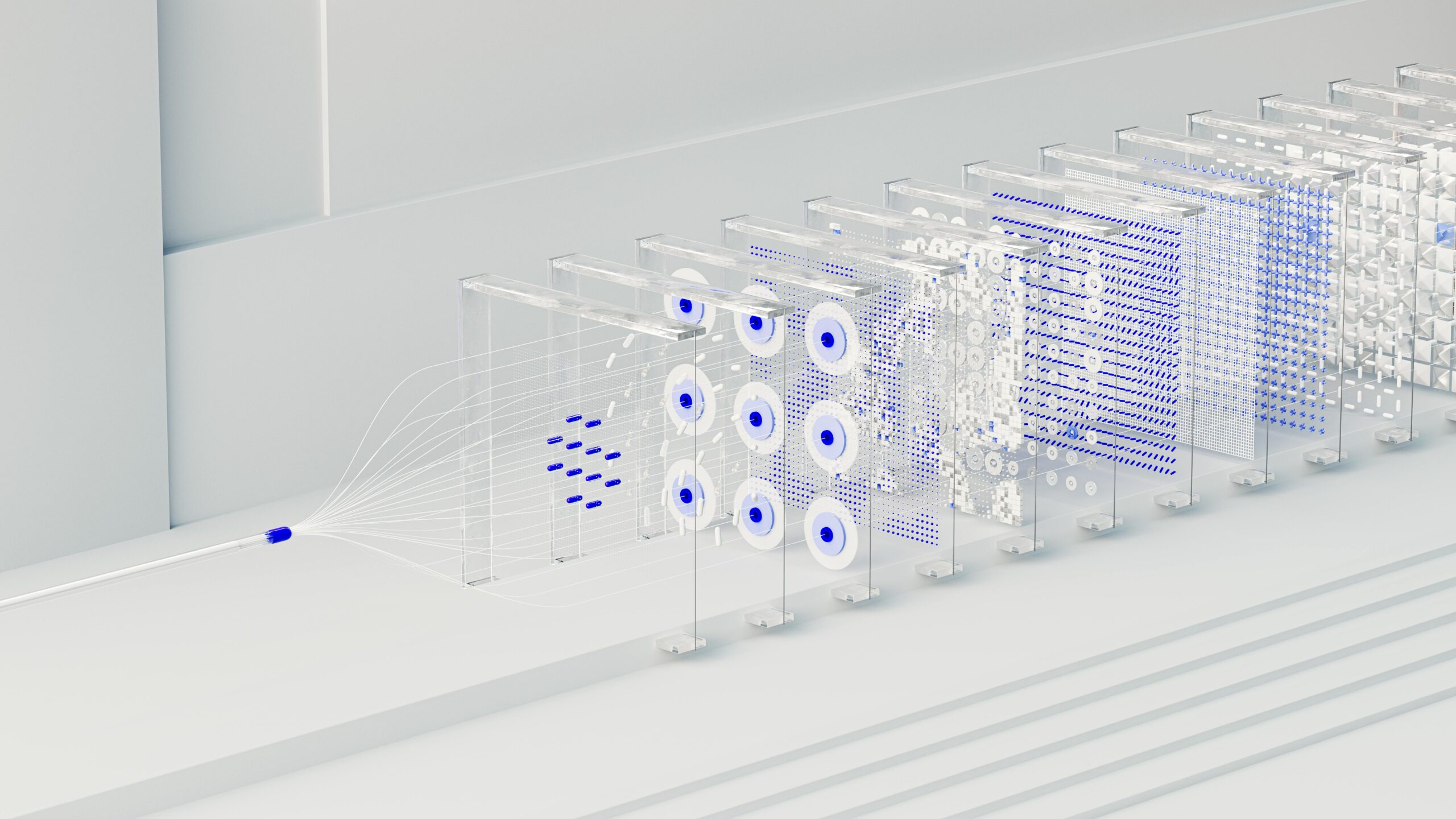

⚙️ Intelligent Power Management Systems

Effective power management extends beyond simply connecting a solar panel to a battery. Sophisticated charge controllers, voltage regulators, and power monitoring systems optimize energy harvesting while protecting batteries from damage.

MPPT vs PWM Charge Controllers

Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) controllers extract 20-30% more energy from solar panels compared to simpler Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) designs, especially valuable when panel voltage significantly exceeds battery voltage or during suboptimal lighting conditions.

MPPT controllers continuously adjust input impedance to operate panels at their maximum power point, converting excess voltage into additional charging current. For small sensor applications, integrated MPPT solutions like the BQ25570 from Texas Instruments provide this functionality in tiny surface-mount packages consuming only microamperes.

PWM controllers remain cost-effective for applications where panel and battery voltages closely match, and where size and efficiency premiums of MPPT don’t justify additional cost. For systems under 5 watts with well-matched components, PWM solutions perform adequately.

Battery Protection Circuits

Lithium batteries require protection against overcharging, over-discharging, overcurrent, and short circuits. Dedicated battery management systems (BMS) monitor individual cell voltages, balance charge distribution in multi-cell packs, and disconnect loads or charging sources when operating limits are approached.

Temperature monitoring prevents charging below freezing—which can permanently damage lithium cells—and disconnects loads or charging at temperature extremes. Quality BMS circuits add minimal quiescent current (typically under 100 µA) while providing essential protection extending battery life from months to years.

🎯 System Integration Best Practices

Combining solar panels, batteries, charge controllers, and sensors into a reliable field system requires attention to electrical design, environmental protection, and maintainability considerations.

Electrical Design Fundamentals

Proper wire sizing minimizes resistive losses that can significantly impact small power systems. For low-voltage systems (3-12V), voltage drop becomes problematic with thin wires over even short distances. Use calculators to ensure wire gauge maintains voltage drop below 3% at maximum current.

Include appropriately rated fuses or polyfuses to protect against short circuits and component failures. Place fuses close to the battery positive terminal to protect wiring throughout the system. Diodes prevent reverse current flow from batteries to panels during darkness, though many modern charge controllers include this protection.

Environmental Enclosure Selection

Field sensors require weatherproof enclosures with appropriate ingress protection ratings. IP65 protects against dust and water jets, suitable for most outdoor applications. IP67 and IP68 provide submersion protection for sensors in flood-prone areas or marine environments.

Transparent or translucent enclosure tops allow solar panels to charge batteries inside protected environments, though light transmission reduces effective panel output by 10-20%. Alternatively, mount panels externally with waterproof cable glands for wire entry.

Ventilation prevents condensation and heat buildup but compromises ingress protection. Gore-Tex vents or similar breathable membranes allow pressure equalization while maintaining water resistance. For sealed enclosures, use desiccant packs to absorb internal moisture.

🌍 Real-world Application Scenarios

Understanding how solar-battery systems perform in diverse field conditions helps design more robust solutions. Different applications present unique challenges requiring tailored approaches.

Agricultural Soil Monitoring Networks

Precision agriculture relies on dense networks of soil moisture, temperature, and nutrient sensors providing continuous data for irrigation optimization. These sensors typically transmit readings every 15-60 minutes using low-power protocols like LoRaWAN, consuming 50-100 mAh daily.

Agricultural installations benefit from unobstructed sunlight exposure but face contamination from dust, chemicals, and irrigation spray. Panels require regular cleaning in dusty environments, as accumulated dirt reduces output by 20-40%. Alternatively, self-cleaning coatings or steeper mounting angles help shed debris naturally.

Wide temperature ranges from below freezing to above 50°C challenge battery chemistry selection. LiFePO4 cells handle temperature extremes better than standard lithium-ion, maintaining performance across agricultural climate zones.

Wildlife Tracking and Conservation

Remote camera traps, acoustic monitors, and environmental sensors enable wildlife research in locations without infrastructure. These applications prioritize long deployment periods (6-12 months) with minimal human intervention that might disturb animals or damage sensitive habitats.

Camera traps present substantial power challenges, as motion detection, imaging, and infrared illumination consume significant energy. Solar panels must be oversized considerably—often 2-5 watts—with battery capacities of 5,000-20,000 mAh to accommodate extended operation and cloudy periods.

Passive infrared (PIR) motion sensors trigger cameras only when animals approach, reducing wasteful imaging of empty scenes. Advanced systems use machine learning to distinguish target species from vegetation movement, further conserving battery power.

Infrastructure and Industrial Monitoring

Sensors monitoring pipeline integrity, structural health, water quality, and equipment conditions require exceptional reliability, as failures may indicate hazardous situations or prevent early problem detection.

These applications often justify premium components—high-efficiency solar panels, industrial-grade batteries, redundant power systems—to maximize uptime. Some critical systems employ dual battery banks alternating charge cycles to ensure continuous operation even during component failures.

Industrial environments may offer shelter from weather but present challenges from electromagnetic interference, vibration, and temperature extremes. Robust mechanical mounting and RF filtering protect sensitive electronics from harsh industrial conditions.

💡 Advanced Energy Harvesting Techniques

Beyond conventional solar panels, emerging energy harvesting technologies supplement or replace photovoltaic systems in specific applications where sunlight proves inadequate or unavailable.

Thermoelectric Generation

Thermoelectric generators (TEGs) convert temperature differentials into electrical energy, useful for sensors mounted on heated equipment, pipelines, or in geothermal environments. Even modest temperature differences of 10-20°C can generate milliwatts sufficient for ultra-low-power sensors.

TEGs require no moving parts and function continuously regardless of lighting conditions, making them ideal for underground or indoor applications. However, efficiency remains low (typically 2-5%), and generation capacity scales with temperature differential and heat transfer area.

Vibration and Kinetic Harvesting

Piezoelectric and electromagnetic harvesters convert mechanical vibration into electricity, applicable to sensors on industrial machinery, bridges, roadways, or other locations with consistent vibration or movement. Output varies tremendously with vibration frequency and amplitude, from microwatts to milliwatts.

These systems complement solar power in environments with limited sunlight but abundant mechanical energy. Railway monitoring sensors, for example, might harvest energy from passing trains while using small backup batteries for periods between trains.

📈 Monitoring and Maintenance Strategies

Even well-designed autonomous systems benefit from remote monitoring and occasional maintenance to ensure continued reliable operation and identify developing issues before failures occur.

Remote Health Monitoring

Transmitting battery voltage, solar charging current, and remaining capacity alongside sensor data provides visibility into power system health. Declining battery voltage trends indicate aging batteries requiring replacement, while reduced solar charging suggests panel cleaning or repositioning needed.

Alert thresholds notify operators when batteries drop below critical levels or charging rates fall outside expected ranges. Proactive intervention prevents sensor downtime and expensive emergency service calls to remote locations.

Preventive Maintenance Schedules

Establishing regular inspection schedules—typically annually or semi-annually—allows cleaning solar panels, checking connection integrity, verifying enclosure seals, and replacing aging batteries before failures occur. Combine sensor visits with other field operations to minimize travel costs and environmental impact.

Documentation of panel output, battery voltage, and environmental conditions during each visit creates historical records revealing long-term trends and informing future system designs. These records prove invaluable when diagnosing intermittent issues or planning capacity upgrades.

🚀 Future Trends in Field Sensor Power Systems

Ongoing technological developments continue improving efficiency, reducing costs, and enabling new applications for solar-powered field sensors.

Advanced Solar Cell Technologies

Perovskite solar cells promise higher efficiency in low-light conditions and flexible form factors enabling integration into curved surfaces or fabric materials. While durability challenges currently limit field deployment, ongoing research addresses stability concerns that will eventually enable commercial applications.

Bifacial solar panels capturing reflected light from both sides increase total energy generation by 10-30% in high-albedo environments like snow-covered fields or light-colored rooftops, potentially reducing required panel size for given applications.

Energy-proportional Computing

Microcontrollers and sensors increasingly implement energy-proportional architectures that scale performance and power consumption to available energy and computational demands. During high solar generation, sensors can increase sampling rates and transmission frequency. When batteries deplete, systems automatically reduce non-essential functions while maintaining core monitoring capabilities.

Machine learning algorithms running on microcontrollers predict solar generation and optimize operational schedules, charging batteries during peak sunlight while deferring power-intensive operations to high-energy periods. This intelligent scheduling maximizes system capabilities within energy constraints.

🔧 Practical Design Guidelines for Your Project

Implementing an effective solar-battery power solution requires systematic design methodology balancing performance requirements, environmental conditions, budget constraints, and maintainability considerations.

Step-by-Step System Design Process

Begin by characterizing your sensor’s complete power profile across all operational modes. Measure actual current consumption rather than relying solely on datasheets, as peripheral circuits and inefficiencies often exceed nominal specifications. Calculate total daily energy requirements including safety margins.

Research solar resources for your deployment location using tools like NREL’s PVWatts calculator or NASA’s Surface meteorology database. Identify worst-case months with minimum solar availability, and design systems to maintain operation during these periods.

Select battery capacity providing adequate autonomy for your reliability requirements. Choose battery chemistry appropriate for expected temperature ranges and cycle life demands. Size solar panels to fully recharge batteries during average worst-month conditions while maintaining sensor operation.

Select charge controller technology matching system scale and budget. Implement battery protection circuits appropriate for chosen chemistry. Design electrical connections minimizing resistance and voltage drop. Choose enclosures providing adequate environmental protection while permitting solar charging.

Testing and Validation

Before field deployment, perform comprehensive bench testing simulating operational conditions. Use programmable power supplies to emulate various solar charging scenarios. Verify battery protection circuits activate at appropriate thresholds. Confirm sensors operate correctly across battery voltage ranges experienced during discharge cycles.

Accelerated lifetime testing identifies potential failure modes before widespread deployment. Subject prototype systems to temperature cycling, humidity exposure, vibration, and extended charge-discharge cycling to validate long-term reliability.

Deploy pilot systems in representative field locations, monitoring performance over complete seasonal cycles before committing to large-scale installations. Real-world validation often reveals issues impossible to anticipate in laboratory environments.

Achieving True Energy Independence in Field Sensing

Solar and battery power solutions have matured from experimental curiosities to proven technologies enabling unprecedented capabilities in environmental monitoring, precision agriculture, and infrastructure management. Modern low-power electronics combined with efficient energy harvesting create truly autonomous systems operating reliably for years without intervention.

Success requires thoughtful system design accounting for worst-case environmental conditions, careful component selection balancing performance and cost, and attention to practical deployment considerations including maintenance accessibility and environmental protection. The investment in proper power system design pays dividends through extended operational life, reduced maintenance costs, and improved data reliability.

As sensor technologies continue advancing toward even lower power consumption, and solar panels become more efficient and affordable, applications previously impossible become routine. The vision of pervasive environmental sensing networks—providing comprehensive real-time data about our natural and built environments—moves steadily from science fiction toward practical reality, powered by sunlight captured and stored through intelligent energy management systems. ☀️

Toni Santos is a bioacoustic researcher and conservation technologist specializing in the study of animal communication systems, acoustic monitoring infrastructures, and the sonic landscapes embedded in natural ecosystems. Through an interdisciplinary and sensor-focused lens, Toni investigates how wildlife encodes behavior, territory, and survival into the acoustic world — across species, habitats, and conservation challenges. His work is grounded in a fascination with animals not only as lifeforms, but as carriers of acoustic meaning. From endangered vocalizations to soundscape ecology and bioacoustic signal patterns, Toni uncovers the technological and analytical tools through which researchers preserve their understanding of the acoustic unknown. With a background in applied bioacoustics and conservation monitoring, Toni blends signal analysis with field-based research to reveal how sounds are used to track presence, monitor populations, and decode ecological knowledge. As the creative mind behind Nuvtrox, Toni curates indexed communication datasets, sensor-based monitoring studies, and acoustic interpretations that revive the deep ecological ties between fauna, soundscapes, and conservation science. His work is a tribute to: The archived vocal diversity of Animal Communication Indexing The tracked movements of Applied Bioacoustics Tracking The ecological richness of Conservation Soundscapes The layered detection networks of Sensor-based Monitoring Whether you're a bioacoustic analyst, conservation researcher, or curious explorer of acoustic ecology, Toni invites you to explore the hidden signals of wildlife communication — one call, one sensor, one soundscape at a time.