As sensors become ubiquitous in our daily environments, from smartphones to smart homes, the intersection of technology and personal privacy demands urgent ethical examination. 🔒

The Silent Observers in Our Daily Lives

Walk into any modern building, and you’re likely surrounded by dozens of sensors collecting data about your presence, movements, and behaviors. These devices range from simple motion detectors to sophisticated cameras with facial recognition capabilities, acoustic sensors that detect conversations, and thermal imaging systems that track body heat signatures. While these technologies promise enhanced convenience, security, and efficiency, they simultaneously raise profound questions about privacy, consent, and human dignity.

The proliferation of sensor technology in spaces where humans live, work, and socialize has outpaced our collective ability to establish ethical frameworks governing their use. Unlike traditional surveillance methods that were often visible and limited in scope, modern sensors can be miniaturized, hidden, and networked to create comprehensive profiles of individuals without their knowledge or explicit consent.

Understanding the Sensor Landscape Around Us

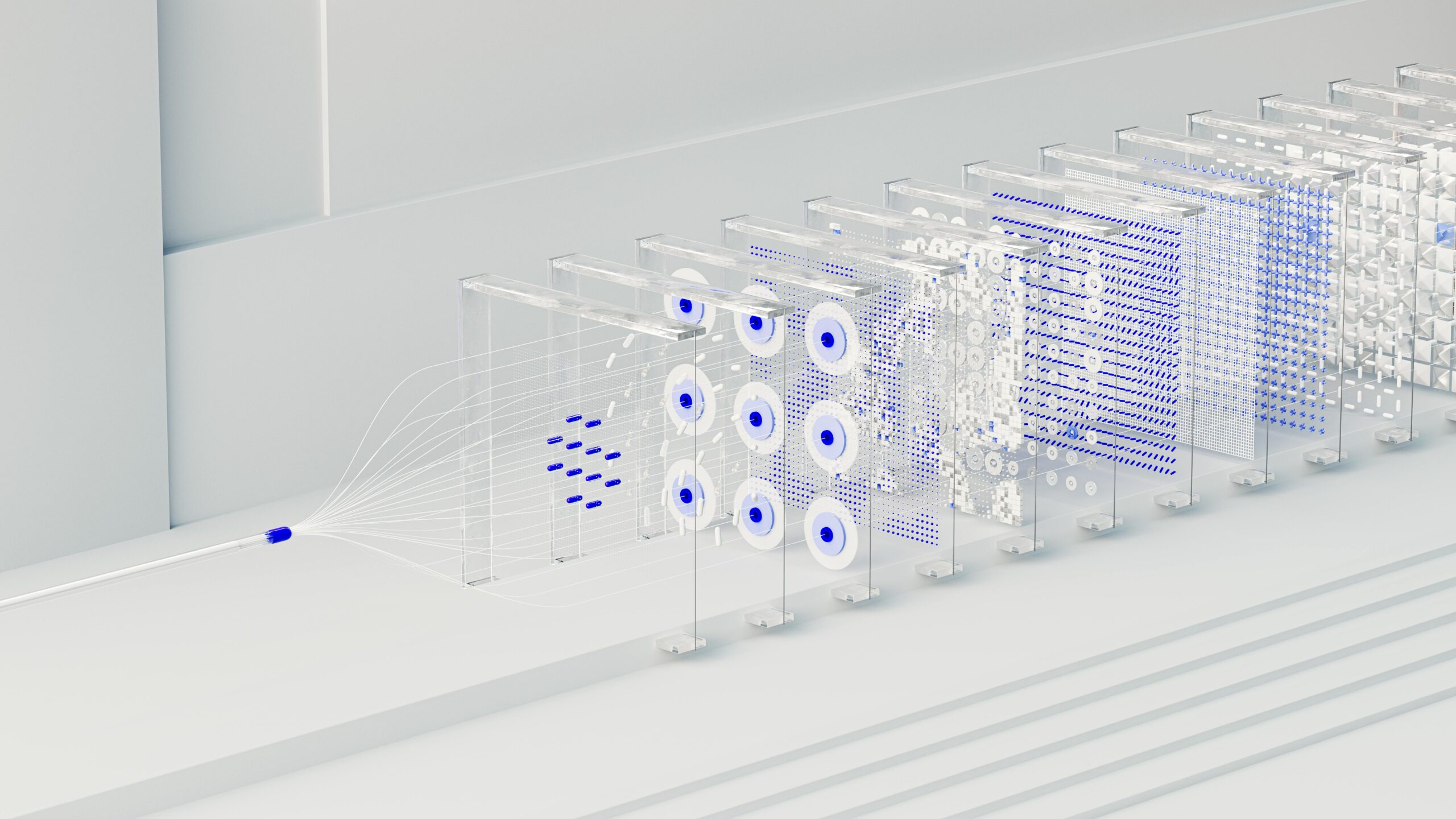

Modern sensor technology encompasses a diverse array of devices, each with unique capabilities and privacy implications. Visual sensors, including cameras and LiDAR systems, can capture detailed images and create three-dimensional maps of spaces. Acoustic sensors can record conversations, identify individuals by voice patterns, and even detect emotional states through voice analysis. Biometric sensors measure physiological data such as heart rate, body temperature, and gait patterns.

Environmental sensors track temperature, humidity, air quality, and occupancy levels in buildings. Location-tracking sensors use GPS, Bluetooth beacons, and Wi-Fi triangulation to pinpoint individuals’ positions with remarkable accuracy. Radio frequency identification (RFID) tags and near-field communication (NFC) devices enable contactless tracking of people and objects throughout various environments.

The Data Collection Ecosystem 📊

These sensors don’t operate in isolation. They’re typically connected to networks that aggregate, analyze, and store the collected data. Machine learning algorithms process this information to identify patterns, make predictions, and generate insights about human behavior. The resulting data can be shared across organizations, sold to third parties, or combined with other datasets to create increasingly detailed profiles of individuals.

The volume of data generated is staggering. A single smart building might collect millions of data points daily, tracking everything from when people enter and exit rooms to how long they spend in certain areas and who they interact with. This granular level of monitoring creates opportunities for both beneficial applications and serious privacy violations.

The Ethical Tensions: Benefits Versus Privacy Rights

The deployment of sensors near human spaces presents genuine benefits that shouldn’t be dismissed. In healthcare settings, sensors can monitor patients’ vital signs, detect falls, and alert caregivers to emergencies. In workplaces, environmental sensors can optimize lighting, heating, and ventilation for comfort and energy efficiency. Security sensors can help prevent crime and enhance public safety in vulnerable areas.

Smart city initiatives use sensors to reduce traffic congestion, improve waste management, and enhance urban planning. In retail environments, sensors help businesses understand customer behavior, optimize store layouts, and reduce theft. These applications demonstrate how sensor technology can improve quality of life, efficiency, and safety.

The Privacy Cost of Convenience

However, these benefits come at a cost. The continuous collection of data about individuals’ movements, behaviors, and activities creates opportunities for surveillance, discrimination, and control. When sensors track employees throughout their workday, the line between productivity monitoring and invasive surveillance blurs. When retailers use facial recognition to identify shoppers, individual autonomy and anonymity in public spaces diminish.

The asymmetry of power in sensor deployment is particularly concerning. Individuals typically have little say in whether sensors are installed in spaces they must occupy—their workplaces, apartment buildings, or public areas. The data collected belongs to the entity that deployed the sensors, not the people being monitored. This creates an imbalance where those being observed have minimal control over how their information is collected, used, or shared.

Consent and Transparency Challenges 🤔

One of the most significant ethical challenges involves obtaining meaningful consent for sensor-based monitoring. In many cases, individuals are unaware that sensors are collecting data about them. Even when notice is provided, it’s often buried in lengthy terms of service documents that few people read or understand. Signs stating “this area is monitored” don’t explain what types of sensors are deployed, what data they collect, how long it’s retained, or who has access to it.

The concept of informed consent requires that people understand what they’re agreeing to and have genuine alternatives. In practice, individuals often face a binary choice: accept monitoring or forfeit access to essential spaces or services. An employee cannot reasonably refuse to enter a workplace fitted with extensive sensor networks. A tenant cannot easily avoid living in a smart building if that’s all that’s available in their price range.

The Illusion of Anonymization

Organizations often claim that collected data is anonymized, suggesting that privacy concerns are mitigated. However, research has repeatedly demonstrated that anonymized datasets can frequently be re-identified, especially when combined with other available information. Gait patterns, movement habits, and behavioral signatures can uniquely identify individuals even without explicit identifiers like names or ID numbers.

Furthermore, the claim that data is “anonymous” provides little comfort when the monitoring itself creates chilling effects on behavior. People may alter their conduct when they know they’re being watched, even if they believe their identity is protected. This self-censorship represents a form of privacy harm that exists independently of whether specific individuals can be identified in datasets.

Workplace Monitoring: When Productivity Meets Surveillance

The workplace represents a particularly complex environment for sensor ethics. Employers have legitimate interests in ensuring productivity, protecting company assets, and maintaining safe working conditions. Sensors can help achieve these goals by tracking equipment usage, monitoring environmental conditions, and analyzing workflow patterns.

However, intensive workplace monitoring can create oppressive environments that undermine employee autonomy, trust, and dignity. When sensors track bathroom breaks, monitor keystrokes, or analyze tone of voice in conversations, they transform workplaces into panopticons where employees feel constantly scrutinized. This level of monitoring can increase stress, reduce job satisfaction, and damage the employer-employee relationship.

The Productivity Paradox

Ironically, excessive monitoring may actually reduce productivity. When employees feel they’re under constant surveillance, they may focus on gaming the metrics rather than doing quality work. Creative problem-solving often requires periods of apparent “unproductivity”—time for reflection, conversation, and experimentation. Sensor systems optimized for constant activity may penalize the very behaviors that lead to innovation and long-term success.

Ethical workplace sensor deployment should involve employee input, clear policies about what’s monitored and why, limitations on data usage, and protections against misuse. Workers should have rights to access data collected about them and challenge inaccurate or unfair interpretations of that data.

Smart Homes: Privacy in Our Most Intimate Spaces 🏠

The home traditionally represents our most private sanctuary—a space where we can be ourselves without external judgment or surveillance. Smart home technology challenges this notion by introducing sensors into our most intimate environments. Voice assistants listen continuously for wake words, smart cameras monitor our movements, and connected appliances track our usage patterns.

While homeowners typically choose to install these devices, the privacy implications extend beyond the purchaser. Family members, guests, and service workers may all be monitored without their explicit consent. Children growing up in sensor-filled homes may never experience privacy as previous generations understood it, potentially normalizing constant surveillance.

Data Beyond the Home

Smart home data doesn’t stay confined to the home. It’s typically transmitted to manufacturers’ servers, where it may be analyzed, aggregated with other users’ data, or shared with third parties. Law enforcement agencies have requested data from smart home devices in criminal investigations, creating tensions between public safety and the sanctity of the home.

Security vulnerabilities in smart home devices present additional risks. Poorly secured sensors can be hacked, giving malicious actors access to intimate details about residents’ lives, schedules, and vulnerabilities. The permanent nature of some recordings creates long-term risks if databases are breached or misused years after the data was collected.

Public Spaces and the Erosion of Anonymity

Public spaces traditionally offered a form of practical anonymity—the ability to move through the world without being identified or tracked. Sensor technology, particularly facial recognition systems, threatens to eliminate this anonymity. Cities worldwide are deploying camera networks that can identify and track individuals as they move through urban environments.

Proponents argue that such systems enhance public safety by helping law enforcement identify criminals and respond to emergencies. Critics counter that the loss of anonymity in public spaces has profound implications for free expression, association, and movement. When every public action is recorded and potentially attributable to a specific individual, people may avoid controversial protests, sensitive medical appointments, or other lawful activities they prefer to keep private.

The Chilling Effect on Democratic Participation 🗳️

The ability to participate anonymously in public life is fundamental to democratic societies. Whistleblowers, political dissidents, and ordinary citizens exercising their rights to protest or organize all depend on some degree of anonymity. Comprehensive sensor networks that eliminate this anonymity can suppress legitimate civic participation, particularly in contexts where governments or powerful private actors might retaliate against those who speak out.

Different societies will draw different boundaries around acceptable public monitoring, reflecting varying cultural values and political systems. However, the decision about where to draw these lines should be made through democratic processes with meaningful public input, not simply by technology companies or government agencies acting unilaterally.

Vulnerable Populations and Disproportionate Impact

Sensor technologies don’t affect all populations equally. Vulnerable groups often face disproportionate monitoring and bear greater risks from sensor deployment. Low-income residents are more likely to live in heavily surveilled public housing. Students in underfunded schools may face more intensive monitoring than their peers in well-resourced institutions. Elderly individuals in care facilities may have virtually no privacy due to comprehensive sensor monitoring.

Algorithmic bias in sensor-based systems can perpetuate discrimination. Facial recognition systems have been shown to perform poorly on people with darker skin tones, potentially leading to misidentification and false accusations. Automated analysis of sensor data may incorporate biased assumptions about what constitutes “normal” or “suspicious” behavior, disadvantaging those who don’t conform to majority patterns.

Power Imbalances and Limited Recourse

Vulnerable populations often have the least power to resist unwanted monitoring or seek redress when their privacy is violated. A tenant in subsidized housing cannot easily refuse to live in a building equipped with extensive sensor networks. A student cannot opt out of school-based monitoring systems. Workers in precarious employment lack the leverage to negotiate privacy protections.

Ethical sensor deployment must consider these power imbalances and include special protections for vulnerable populations. This might include stricter limitations on monitoring in contexts where individuals lack genuine alternatives, enhanced transparency requirements, and accessible mechanisms for challenging privacy violations.

Regulatory Frameworks and Governance Approaches ⚖️

Existing privacy laws often struggle to address the unique challenges posed by sensor technology. Regulations developed for traditional data collection methods may not adequately cover continuous, ambient monitoring. Some jurisdictions have begun developing more comprehensive frameworks that specifically address sensor-based surveillance.

The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) establishes principles that apply to sensor data, including requirements for lawful basis, data minimization, and purpose limitation. California’s Consumer Privacy Act and similar state laws in the United States provide some protections, though the fragmented regulatory landscape creates inconsistencies.

Elements of Effective Sensor Governance

Comprehensive governance frameworks for sensors near human spaces should include several key elements. First, transparency requirements that mandate clear disclosure of what sensors are deployed, what data they collect, and how it’s used. Second, meaningful consent mechanisms that give individuals genuine choice about participation in sensor-based monitoring, particularly in non-essential contexts.

Third, data minimization principles that limit collection to what’s genuinely necessary for stated purposes, with defined retention periods and secure deletion procedures. Fourth, purpose limitation rules that prevent sensor data from being repurposed without additional authorization. Fifth, accountability mechanisms that include regular audits, impact assessments, and consequences for violations.

Building an Ethical Framework for Sensor Deployment 🛠️

Organizations deploying sensors near human spaces should adopt ethical frameworks that go beyond legal compliance. These frameworks should start with necessity assessment: is the sensor genuinely needed to achieve a legitimate objective that cannot be accomplished through less privacy-invasive means? If so, how can the deployment be designed to minimize privacy impact while achieving its goals?

Privacy impact assessments should be conducted before sensors are deployed, identifying potential harms and mitigation strategies. These assessments should consider not just legal compliance but broader ethical implications, including effects on human dignity, autonomy, and social relationships. Stakeholders who will be affected by the monitoring should participate in these assessments.

Design Principles for Privacy-Respecting Sensors

Privacy-by-design principles can guide sensor deployment to minimize privacy risks. This includes technical measures like local data processing rather than cloud transmission, encryption of collected data, and automatic deletion of information after defined periods. Functional limitations can be built into sensors—for example, using presence detection rather than cameras, or deliberately reducing image resolution to prevent facial recognition while still achieving monitoring objectives.

Organizations should establish clear governance structures with defined responsibilities for sensor oversight, regular reviews of deployment decisions, and accessible complaint mechanisms. Privacy advocates or representatives of monitored populations should have meaningful roles in oversight processes, not just token participation.

The Path Forward: Balancing Innovation and Human Rights

Sensor technology will continue advancing, becoming more capable, ubiquitous, and integrated into our environments. The question isn’t whether these technologies will exist, but how we’ll govern them to protect fundamental human rights while enabling beneficial applications. This requires ongoing dialogue among technologists, policymakers, ethicists, and the public.

We need robust public debate about where lines should be drawn—which spaces should remain sensor-free zones, what types of data collection should be prohibited regardless of consent, and how to ensure accountability when privacy violations occur. These conversations must happen at local, national, and international levels, as sensor networks often cross jurisdictional boundaries.

Individual Agency and Collective Action 💪

While systemic solutions through regulation and institutional reform are essential, individuals can take steps to protect their privacy in sensor-rich environments. This includes being informed about what sensors exist in spaces they frequent, understanding privacy settings on personal devices, and advocating for stronger protections in workplaces, schools, and communities.

Collective action through privacy advocacy organizations, unions, and community groups can amplify individual voices and push for systemic change. Supporting legislation that strengthens privacy protections, participating in public comment processes on surveillance proposals, and choosing to patronize businesses that respect privacy all contribute to building a culture that values privacy as a fundamental right.

Reimagining Technology That Serves Humanity

Ultimately, the ethical challenge of sensors near human spaces invites us to reimagine our relationship with technology. Rather than accepting surveillance as an inevitable byproduct of innovation, we can demand technologies designed to serve human flourishing, dignity, and autonomy. This means prioritizing privacy-preserving approaches, ensuring meaningful human control over data collection, and maintaining spaces where people can exist free from monitoring.

The sensors surrounding us should enhance our lives without diminishing our humanity. Achieving this balance requires vigilance, advocacy, and commitment to ethical principles that place human rights at the center of technological development. As we navigate this sensor-saturated landscape, the choices we make today will shape the kind of society future generations inherit—one where privacy is protected as a fundamental value, or one where surveillance becomes inescapable.

The conversation about sensors and privacy isn’t just a technical discussion for experts—it affects everyone who lives in modern societies. By engaging with these questions thoughtfully and demanding accountability from those who deploy sensor technologies, we can work toward a future where innovation and privacy coexist, where technology serves human needs without compromising human dignity, and where the spaces we inhabit remain places where we can truly be ourselves. 🌟

Toni Santos is a bioacoustic researcher and conservation technologist specializing in the study of animal communication systems, acoustic monitoring infrastructures, and the sonic landscapes embedded in natural ecosystems. Through an interdisciplinary and sensor-focused lens, Toni investigates how wildlife encodes behavior, territory, and survival into the acoustic world — across species, habitats, and conservation challenges. His work is grounded in a fascination with animals not only as lifeforms, but as carriers of acoustic meaning. From endangered vocalizations to soundscape ecology and bioacoustic signal patterns, Toni uncovers the technological and analytical tools through which researchers preserve their understanding of the acoustic unknown. With a background in applied bioacoustics and conservation monitoring, Toni blends signal analysis with field-based research to reveal how sounds are used to track presence, monitor populations, and decode ecological knowledge. As the creative mind behind Nuvtrox, Toni curates indexed communication datasets, sensor-based monitoring studies, and acoustic interpretations that revive the deep ecological ties between fauna, soundscapes, and conservation science. His work is a tribute to: The archived vocal diversity of Animal Communication Indexing The tracked movements of Applied Bioacoustics Tracking The ecological richness of Conservation Soundscapes The layered detection networks of Sensor-based Monitoring Whether you're a bioacoustic analyst, conservation researcher, or curious explorer of acoustic ecology, Toni invites you to explore the hidden signals of wildlife communication — one call, one sensor, one soundscape at a time.