Wildlife conservation sits at a critical crossroads where technology, ethics, and environmental stewardship intersect. Modern recording and indexing methods present unprecedented opportunities alongside complex moral questions that demand our attention.

🌍 The Digital Revolution in Wildlife Monitoring

The technological transformation of wildlife conservation has fundamentally altered how researchers, conservationists, and policymakers approach species protection. Camera traps, GPS tracking devices, acoustic sensors, and drone technology now generate massive amounts of data about animal populations, behaviors, and habitats. This information revolution enables real-time monitoring of endangered species, migration pattern analysis, and rapid response to conservation threats.

Digital indexing systems have become the backbone of modern conservation efforts. Databases like the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) and various regional wildlife registries compile millions of species observations annually. These systems facilitate collaboration across borders, enable predictive modeling for habitat management, and provide crucial evidence for policy decisions affecting protected areas.

However, this data abundance creates an ethical paradox. While information accessibility promotes transparency and scientific advancement, it simultaneously exposes vulnerable species to potential exploitation. The same location data that helps researchers track endangered rhinoceros populations could guide poachers to their targets. This duality forces conservationists to navigate treacherous ethical terrain with every recording and indexing decision.

🔍 Privacy Paradox: When Protection Requires Secrecy

The concept of privacy extends beyond human subjects into wildlife conservation ethics. Detailed location data for critically endangered species represents a double-edged sword. Published research and open-access databases traditionally advance scientific knowledge democratically, yet this transparency can inadvertently weaponize information against the very species researchers aim to protect.

Several high-profile cases illustrate these dangers. Geotagged photographs of rare bird nests have led to egg collectors descending on previously undisturbed sites. Published den locations for wolverines and wolves have resulted in targeted killings. Even well-intentioned nature enthusiasts sharing social media posts about rare species sightings have created problems, as crowds of photographers disturb sensitive breeding areas.

Conservation organizations now implement tiered access systems for sensitive data. Core location information remains restricted to verified researchers and law enforcement, while generalized distribution data becomes publicly available. This approach balances scientific transparency with species security, though it raises questions about who decides access criteria and whether such gatekeeping contradicts open science principles.

Balancing Act: Data Sharing Protocols

Effective data governance requires nuanced protocols that consider species vulnerability, regional threats, and stakeholder needs. Many institutions now employ geographic obfuscation techniques, reporting species presence within broad areas rather than precise coordinates. Temporal delays in data publication provide additional protection, ensuring animals have moved before locations become public knowledge.

These protective measures must be proportional to actual risks. Overly restrictive data policies can hamper legitimate conservation work, preventing collaboration and slowing scientific progress. Finding the appropriate balance requires ongoing dialogue between field researchers, database administrators, law enforcement agencies, and local communities invested in conservation outcomes.

📱 Technology’s Double-Edged Impact on Conservation Ethics

Mobile applications have democratized wildlife observation, transforming casual nature enthusiasts into citizen scientists. Platforms like iNaturalist, eBird, and Seek enable millions of users to record and share species observations, creating unprecedented datasets for biodiversity research. These crowdsourced initiatives provide valuable distribution information for common species and can detect range expansions or population shifts faster than traditional surveys.

Yet citizen science platforms introduce ethical complexities around data quality, participant education, and unintended consequences. Inexperienced observers may misidentify species, creating false distribution records that mislead conservation planning. Well-meaning participants might approach wildlife too closely for photographs, causing stress or behavioral disruption. Popular species become targets for “digital trophy hunting,” where rare sightings drive enthusiasts to seek out sensitive animals for documentation.

The gamification of wildlife observation presents particular challenges. When platforms award badges, rankings, or recognition for rare species observations, they may inadvertently incentivize behavior that prioritizes personal achievement over animal welfare. Conservation educators must cultivate ethical observation practices alongside technical identification skills.

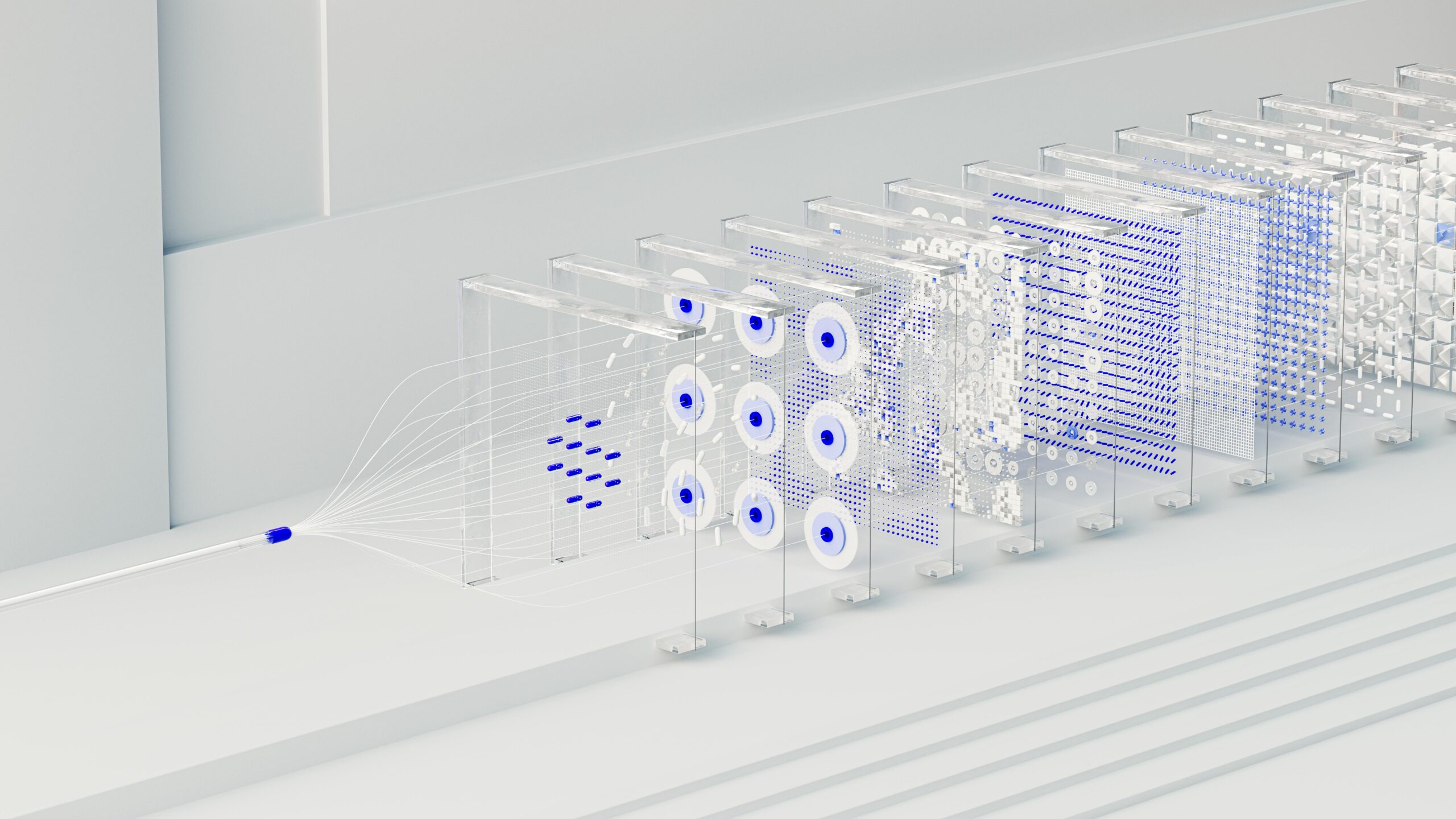

Artificial Intelligence: Promise and Peril

Machine learning algorithms now automatically identify species from camera trap images, analyze acoustic recordings for specific animal calls, and process satellite imagery to detect habitat changes. These AI systems dramatically reduce the labor required for data processing, enabling conservation projects to operate at previously impossible scales.

However, AI-powered wildlife monitoring raises questions about bias, accuracy, and autonomy. Training datasets often reflect geographic and taxonomic biases, potentially creating blind spots for underrepresented species or regions. Algorithmic errors could lead to misallocated conservation resources or overlooked threats. The increasing automation of wildlife monitoring also risks distancing conservationists from direct field experience, potentially diminishing the contextual understanding that informs ethical decision-making.

🌿 Indigenous Knowledge and Data Sovereignty

Traditional ecological knowledge represents millennia of careful observation and relationship-building with local ecosystems. Indigenous communities often possess detailed understanding of species behaviors, habitat requirements, and ecosystem dynamics that complement or exceed scientific knowledge. Yet historical patterns of data extraction have seen researchers collect this knowledge without appropriate recognition, consent, or benefit-sharing.

Data sovereignty principles assert that communities have rights to control information about their territories and cultural heritage. For wildlife conservation, this means recognizing indigenous peoples as knowledge holders and decision-makers rather than merely data sources. Ethical recording and indexing practices must respect traditional governance structures, obtain free prior informed consent, and establish equitable partnerships that benefit local communities.

Several innovative projects demonstrate how indigenous-led conservation can integrate traditional knowledge with modern technology. Community-managed monitoring programs employ local rangers who combine ancestral tracking skills with GPS devices and smartphones. These initiatives often achieve superior conservation outcomes while supporting local livelihoods and cultural continuity.

Cultural Sensitivity in Species Documentation

Certain animals hold sacred or culturally sensitive status within indigenous worldviews. Publishing detailed information about these species without community consultation may violate cultural protocols or spiritual beliefs. Ethical conservation practice requires cultural competency and willingness to modify standard documentation procedures when they conflict with local values.

This cultural dimension extends to naming conventions and taxonomic classification. Scientific binomial nomenclature may ignore or erase indigenous names that encode ecological relationships and cultural significance. Inclusive indexing systems incorporate multiple naming traditions, recognizing diverse ways of knowing and relating to wildlife.

💼 Commercial Interests and Conservation Data

The commodification of wildlife data presents ethical challenges as private companies increasingly participate in conservation technology. Commercial camera trap systems, genetic sequencing services, and data analysis platforms offer sophisticated tools that advance conservation capacity. However, profit motives don’t always align with conservation ethics, creating potential conflicts around data ownership, access costs, and privacy.

Pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies show interest in genetic databases for bioprospecting potential medical compounds or agricultural applications. While such research might yield valuable innovations, it raises questions about benefit-sharing with countries of origin and communities stewarding biodiversity. International protocols like the Nagoya Protocol attempt to address these concerns, but implementation remains inconsistent.

Ecotourism operators represent another commercial stakeholder group with complex relationships to wildlife data. Location information about charismatic species drives tourism revenue that can fund conservation programs and local development. However, tourism pressure can disturb wildlife, degrade habitats, and create economic dependencies that prioritize visitor access over ecological needs.

⚖️ Legal Frameworks and Ethical Guidelines

International agreements provide foundation for wildlife conservation ethics, though gaps remain between legal requirements and ethical best practices. The Convention on Biological Diversity establishes principles for equitable benefit-sharing and conservation cooperation. CITES regulates international trade in endangered species, relying heavily on documentation and monitoring data.

National legislation varies dramatically in wildlife data protection. Some countries classify endangered species location data as confidential, while others maintain completely open systems. These legal differences create challenges for international collaboration and can leave species vulnerable when they cross jurisdictional boundaries.

Professional organizations have developed ethical guidelines for wildlife research and documentation. The Wildlife Society, International Association of Impact Assessment, and various taxonomic specialist groups maintain codes of conduct addressing data management, field methodology, and stakeholder engagement. However, these guidelines generally lack enforcement mechanisms, relying on professional norms and peer accountability.

Emerging Regulatory Challenges

Rapid technological advancement outpaces regulatory development, creating ethical gray zones around new conservation tools. Drone surveillance, environmental DNA sampling, and social media monitoring raise privacy questions that existing frameworks don’t adequately address. International cooperation becomes essential as wildlife and data flows ignore national borders.

Data protection regulations like Europe’s GDPR primarily address human privacy but set precedents for information governance that may inform wildlife data management. Concepts like data minimization, purpose limitation, and right to erasure could adapt to conservation contexts, though their application to non-human subjects requires careful consideration.

🔬 Scientific Integrity in the Digital Age

The permanent, searchable nature of digital records elevates stakes for data accuracy and responsible reporting. Errors or fraudulent data, once indexed in major databases, can persist indefinitely and propagate through derivative analyses. Conservation decisions based on flawed information may waste limited resources or even harm species they intend to protect.

Pressure to publish novel findings and generate continuous data streams can incentivize rushed or incomplete work. The “publish or perish” culture of academic research sometimes conflicts with the careful, long-term observation that wildlife conservation requires. Ethical practice demands prioritizing data quality over quantity, even when this conflicts with career advancement pressures.

Replication and verification present particular challenges for wildlife observations, which often involve rare events or difficult-to-access locations. Establishing robust peer review processes for citizen science data, ensuring metadata completeness, and maintaining version control for database updates all contribute to scientific integrity.

🌟 Toward Ethical Futures in Wildlife Conservation

Addressing these multifaceted ethical challenges requires adaptive, inclusive approaches that center conservation outcomes while respecting diverse values and knowledge systems. No single solution fits all contexts; rather, ethical frameworks must remain flexible enough to accommodate regional differences, species-specific needs, and evolving circumstances.

Education represents a critical lever for improving conservation ethics. Training programs should integrate ethical reasoning alongside technical skills, preparing researchers and practitioners to navigate complex dilemmas. Public education initiatives can foster responsible wildlife observation practices among citizen scientists and nature enthusiasts.

Meaningful stakeholder engagement ensures that diverse perspectives inform conservation decisions. Indigenous communities, local residents, field researchers, database managers, policymakers, and funding organizations all bring valuable insights to ethical deliberations. Creating spaces for ongoing dialogue helps identify conflicts early and develop collaborative solutions.

Building Trustworthy Systems

Trust forms the foundation for effective conservation data systems. Transparent governance structures, clear data use policies, and accountable decision-making processes help build confidence among contributors and users. Regular ethics audits can identify emerging concerns and ensure practices align with stated values.

Technological solutions like blockchain for data provenance, differential privacy techniques for protecting sensitive information, and federated learning for collaborative analysis without centralized data storage may address some ethical challenges. However, technology alone cannot resolve fundamentally values-based questions about appropriate data use and conservation priorities.

🦋 Cultivating Conservation Ethics as Living Practice

Wildlife conservation ethics cannot remain static in rapidly changing technological and social landscapes. Regular reflection, open dialogue, and willingness to revise practices distinguish ethical conservationists from those merely following established procedures. The uncomfortable questions around data sharing, stakeholder rights, and competing values deserve continuous attention rather than one-time resolution.

Future conservation professionals must develop ethical literacy alongside technical expertise, recognizing that their data management decisions carry real consequences for species survival and human communities. By embracing complexity rather than seeking simplistic solutions, the conservation community can navigate ethical dilemmas while advancing toward a more sustainable and just future for wildlife and people alike.

The path forward requires humility about uncertainty, respect for diverse perspectives, and commitment to transparent, accountable practice. Wildlife conservation’s ethical challenges will evolve with new technologies and social changes, demanding ongoing vigilance and adaptation. Through thoughtful engagement with these difficult questions, conservationists can harness the power of recording and indexing technologies while honoring the profound responsibility that comes with documenting Earth’s magnificent biodiversity.

Toni Santos is a bioacoustic researcher and conservation technologist specializing in the study of animal communication systems, acoustic monitoring infrastructures, and the sonic landscapes embedded in natural ecosystems. Through an interdisciplinary and sensor-focused lens, Toni investigates how wildlife encodes behavior, territory, and survival into the acoustic world — across species, habitats, and conservation challenges. His work is grounded in a fascination with animals not only as lifeforms, but as carriers of acoustic meaning. From endangered vocalizations to soundscape ecology and bioacoustic signal patterns, Toni uncovers the technological and analytical tools through which researchers preserve their understanding of the acoustic unknown. With a background in applied bioacoustics and conservation monitoring, Toni blends signal analysis with field-based research to reveal how sounds are used to track presence, monitor populations, and decode ecological knowledge. As the creative mind behind Nuvtrox, Toni curates indexed communication datasets, sensor-based monitoring studies, and acoustic interpretations that revive the deep ecological ties between fauna, soundscapes, and conservation science. His work is a tribute to: The archived vocal diversity of Animal Communication Indexing The tracked movements of Applied Bioacoustics Tracking The ecological richness of Conservation Soundscapes The layered detection networks of Sensor-based Monitoring Whether you're a bioacoustic analyst, conservation researcher, or curious explorer of acoustic ecology, Toni invites you to explore the hidden signals of wildlife communication — one call, one sensor, one soundscape at a time.