Acoustic monitoring has emerged as a powerful tool to assess and understand the profound ways human activities reshape natural soundscapes and ecosystems worldwide.

🔊 The Symphony of Science: What Acoustic Monitoring Reveals

Our planet produces a constant orchestra of sounds—from whale songs echoing through ocean depths to the rustling of insects in tropical forests. These natural soundscapes have evolved over millennia, creating acoustic niches where species communicate, hunt, and survive. However, human activities are fundamentally altering this ancient symphony, and scientists are using acoustic monitoring to document these changes with unprecedented precision.

Acoustic monitoring involves deploying recording devices in various environments to capture sound data over extended periods. This non-invasive technique allows researchers to evaluate biodiversity, detect species presence, monitor ecosystem health, and quantify human impact without disturbing wildlife. The technology has revolutionized conservation biology, offering insights that traditional observation methods simply cannot match.

The data collected through acoustic sensors reveals patterns invisible to the naked eye. Researchers can identify individual species by their unique vocalizations, track migration patterns, detect illegal activities like poaching or logging, and measure the acoustic footprint of human infrastructure. This information becomes crucial for environmental policy, conservation planning, and understanding the cascading effects of anthropogenic change.

Decoding Nature’s Audio Library 📚

Every ecosystem possesses a distinct acoustic signature—what soundscape ecologists call a “soundscape.” These soundscapes comprise three main components: biophony (sounds from living organisms), geophony (sounds from natural non-biological sources like wind and water), and anthrophony (human-generated sounds). The balance between these elements indicates ecosystem health and human impact levels.

In pristine environments, biophony dominates during active periods, with diverse species creating layered acoustic textures. Birds occupy specific frequency bands, insects fill others, and mammals contribute deeper tones. This acoustic partitioning represents millions of years of evolutionary adaptation, allowing multiple species to communicate simultaneously without interference.

When humans enter these environments, the acoustic balance shifts dramatically. Roads introduce constant low-frequency rumble, industrial activities add mechanical noise, and urban expansion creates persistent sound pollution. These changes don’t merely add noise—they actively disrupt communication networks that countless species depend upon for survival.

The Mechanics of Modern Acoustic Research

Contemporary acoustic monitoring relies on sophisticated autonomous recording units (ARUs) that can operate for months in remote locations. These devices capture high-quality audio across frequencies ranging from infrasound (below human hearing) to ultrasound (above human hearing). This broad spectrum coverage ensures researchers don’t miss important signals, whether elephant rumbles at 14 Hz or bat echolocation calls at 120 kHz.

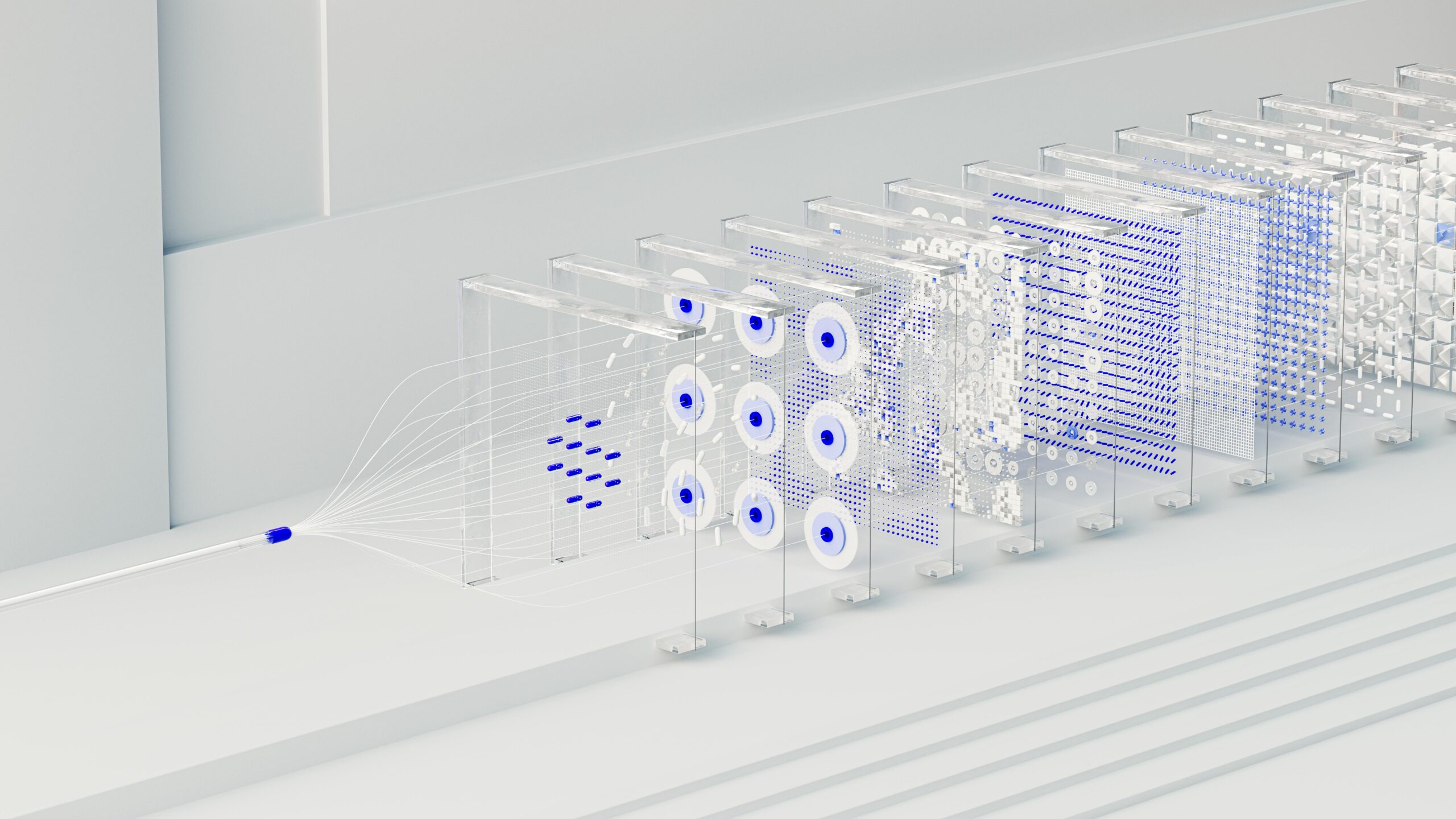

The real challenge comes after data collection. A single recording unit operating continuously for one month generates approximately 720 hours of audio data. Analyzing this manually would be impossible, so researchers employ machine learning algorithms and artificial intelligence to identify patterns, classify sounds, and flag events of interest. These computational tools have transformed acoustic ecology from an anecdotal science into a data-driven discipline.

🌊 Marine Environments: Underwater Acoustic Disruption

Ocean soundscapes face perhaps the most severe acoustic pollution on Earth. Shipping traffic has increased ambient ocean noise levels by up to 32 times in some regions since pre-industrial times. This noise operates primarily in low frequencies—the same range that many marine mammals use for long-distance communication.

Whales, which once communicated across entire ocean basins, now struggle to hear each other over distances of just kilometers in busy shipping lanes. Studies using hydrophone arrays have documented how North Atlantic right whales have increased their call amplitude by 6 decibels over recent decades—essentially shouting to be heard over human-generated noise. This vocal strain requires additional energy expenditure and still doesn’t fully compensate for reduced communication range.

Sonar systems used by military and commercial vessels create intense acoustic pulses that can cause physical trauma to marine life. Mass strandings of beaked whales have been directly linked to naval exercises, with acoustic monitoring providing the forensic evidence needed to establish these connections. The data reveals that these deep-diving species are particularly vulnerable to mid-frequency active sonar, which can cause decompression sickness-like symptoms.

Mapping Acoustic Dead Zones

Researchers have created acoustic maps of marine environments, revealing “dead zones” where biological sounds are overwhelmed by human noise. In these areas, critical life functions become compromised. Fish that rely on sound to locate spawning grounds may fail to reproduce. Larvae that use acoustic cues to find suitable settlement habitat drift into unsuitable areas. Predators that depend on passive listening to locate prey experience reduced hunting success.

The impact extends beyond individual species to entire food webs. Acoustic monitoring in coral reefs demonstrates that healthy reefs produce a rich tapestry of sounds—snapping shrimp, grunting fish, and various invertebrates create what’s been termed the “reef orchestra.” Degraded reefs fall silent. This acoustic signature allows researchers to assess reef health remotely and track restoration success over time.

Terrestrial Ecosystems Under Acoustic Pressure 🌲

Land-based ecosystems face different but equally significant acoustic challenges. Road noise represents one of the most pervasive forms of terrestrial acoustic pollution, affecting habitats up to several kilometers from highways. Birds living near roads sing at higher frequencies and increased volumes to overcome traffic noise—an adaptation that requires energy and may reduce reproductive success.

Acoustic monitoring in forests adjacent to roads reveals patterns of acoustic masking, where critical communication signals become imperceptible against background noise. Frog choruses shift their timing to quieter periods, but this forces them into temperature ranges that may be suboptimal for calling. Predators that hunt by sound experience reduced foraging efficiency, potentially altering predator-prey dynamics throughout the ecosystem.

Extractive industries like mining, logging, and oil drilling create intense localized noise pollution. Acoustic recordings from areas near these operations show dramatic reductions in vocal activity from sensitive species and shifts in community composition toward noise-tolerant generalists. This acoustic sorting creates simplified ecosystems with reduced biodiversity and compromised ecological functions.

Urban Sprawl and the Acoustic Refuge Crisis

Cities represent extreme acoustic environments where human sounds dominate virtually all frequencies throughout most of the 24-hour cycle. Urban acoustic monitoring reveals that only the most adaptable species persist—those that can adjust their communication systems to exploit narrow acoustic windows or shift to visual signals.

However, urban areas also create unexpected experimental opportunities. Researchers studying cities as acoustic gradients have discovered that noise pollution acts as a selective pressure, driving rapid evolutionary changes in vocal behavior. Some bird populations have evolved distinctly different songs in just a few generations, with urban birds producing higher-pitched, faster-paced songs than their rural counterparts.

📊 Quantifying the Acoustic Footprint

Measuring human acoustic impact requires standardized metrics. Researchers use several key indicators:

- Acoustic Complexity Index (ACI): Measures the variability of sound intensities, with higher values typically indicating greater biodiversity

- Normalized Difference Soundscape Index (NDSI): Compares the ratio of biological sounds to human-generated sounds

- Acoustic Diversity Index (ADI): Quantifies the evenness of sound distribution across frequency bands

- Bio-acoustic Event Rate: Counts the frequency of biological vocalizations per unit time

- Acoustic Space Occupancy: Measures the proportion of acoustic frequencies being actively used

These metrics allow researchers to compare acoustic conditions across sites, track changes over time, and establish baseline conditions for monitoring human impact. They also facilitate large-scale meta-analyses that reveal global patterns of acoustic degradation and identify particularly vulnerable ecosystems or species.

🛠️ Technology Driving Acoustic Conservation

The field of acoustic monitoring has benefited enormously from technological advances. Modern recording units are weatherproof, solar-powered, and capable of storing weeks of high-quality audio data. Costs have decreased dramatically, making large-scale deployment feasible even for projects with modest budgets.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms have revolutionized data analysis. Convolutional neural networks trained on labeled audio data can now identify species with accuracy rivaling or exceeding human experts. These algorithms can process months of recordings in hours, detecting rare species, flagging unusual events, and quantifying acoustic indices automatically.

Cloud-based platforms now allow real-time acoustic monitoring, where recordings upload automatically via cellular networks. Conservation managers receive immediate alerts when acoustic sensors detect gunshots (indicating poaching), chainsaw sounds (illegal logging), or vehicle engines (unauthorized access). This real-time capability transforms acoustic monitoring from a research tool into an active conservation intervention.

Citizen Science and Acoustic Engagement

Mobile applications have democratized acoustic monitoring, allowing citizens to contribute valuable data. While these apps vary in sophistication, they engage public interest in soundscape ecology and create distributed monitoring networks that complement professional research efforts. Audio recordings from hundreds or thousands of citizen scientists can reveal patterns across vast geographic scales that would be impossible for individual research teams to document.

Case Studies: Acoustic Monitoring in Action 🔍

Several high-profile projects demonstrate the power of acoustic monitoring for understanding human impact. In the Amazon rainforest, researchers deployed acoustic sensors across a gradient from pristine forest to agricultural land. The data revealed that species richness declined predictably with increasing human disturbance, but some acoustic niches remained filled by generalist species, masking biodiversity loss when using simple abundance metrics.

In Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, underwater acoustic monitoring documented coral reef recovery following protection measures. As fish populations rebounded, the characteristic sounds of healthy reefs returned—providing an auditory measure of conservation success that complemented visual surveys and offered insights into nocturnal activity patterns previously difficult to study.

North American prairies have been monitored acoustically to assess grassland bird population trends. These species are among the continent’s fastest-declining bird groups, and traditional surveys miss many individuals. Acoustic monitoring revealed that human presence during surveys caused many birds to stop singing, meaning traditional counts systematically underestimated populations and missed the full extent of human impact.

🌍 Policy Implications and Conservation Planning

Acoustic monitoring data increasingly informs environmental policy and conservation decisions. The evidence of noise pollution’s ecological impacts has led some jurisdictions to establish acoustic protected areas where human-generated sound is regulated or prohibited during sensitive periods. These “quiet zones” provide acoustic refuges where species can maintain normal communication and behavior patterns.

Environmental impact assessments now routinely include acoustic components, requiring developers to measure and mitigate noise pollution from proposed projects. Before-and-after acoustic monitoring documents whether mitigation measures actually work, creating accountability and driving improvements in practices that reduce acoustic footprints.

International conservation organizations use acoustic monitoring to prioritize protection efforts. Areas with high acoustic diversity often harbor significant biodiversity, making them conservation priorities. Conversely, acoustically degraded areas may require active restoration interventions to recover ecological function.

Confronting the Challenges Ahead 🚀

Despite remarkable progress, acoustic monitoring faces significant challenges. Standardizing methods across research groups remains difficult, complicating efforts to compare results or conduct meta-analyses. The sheer volume of data generated can overwhelm storage systems and analysis pipelines, particularly for smaller research teams or conservation organizations.

Interpretation challenges persist as well. Not all human sounds negatively impact wildlife—some species adapt successfully or even benefit from anthropogenic changes. Distinguishing between harmless acoustic alteration and genuine ecological disruption requires careful analysis and long-term monitoring to detect population-level consequences.

Climate change adds another layer of complexity. As temperature and precipitation patterns shift, species ranges move, and phenology changes, the acoustic baselines we’ve established may become obsolete. Acoustic monitoring must evolve to track these dynamic changes while continuing to assess human impacts.

Tuning Into Tomorrow’s Solutions 🎯

The future of acoustic monitoring holds exciting possibilities. Advances in sensor technology will enable even smaller, cheaper, and more capable recording devices. Integration with other sensors—cameras, weather stations, and environmental probes—will provide richer contextual data to interpret acoustic patterns.

Machine learning algorithms will become more sophisticated, capable of detecting subtle changes in animal vocalizations that indicate stress, disease, or changing environmental conditions. Real-time analysis will expand, providing immediate feedback for adaptive management decisions.

Most importantly, acoustic monitoring will continue revealing the profound ways human activities reshape the soundscapes our planet’s species depend upon. By making these impacts audible and quantifiable, acoustic ecology builds the evidence base needed for meaningful conservation action. The alarm has sounded—now we must listen and respond.

As human populations grow and our footprint expands, understanding and mitigating acoustic impacts becomes increasingly critical. The technology exists, the methods are established, and the data are compelling. What remains is the collective will to protect not just the visual beauty of our natural world, but its acoustic richness—the sounds that have defined our planet for millennia and must continue into the future.

Toni Santos is a bioacoustic researcher and conservation technologist specializing in the study of animal communication systems, acoustic monitoring infrastructures, and the sonic landscapes embedded in natural ecosystems. Through an interdisciplinary and sensor-focused lens, Toni investigates how wildlife encodes behavior, territory, and survival into the acoustic world — across species, habitats, and conservation challenges. His work is grounded in a fascination with animals not only as lifeforms, but as carriers of acoustic meaning. From endangered vocalizations to soundscape ecology and bioacoustic signal patterns, Toni uncovers the technological and analytical tools through which researchers preserve their understanding of the acoustic unknown. With a background in applied bioacoustics and conservation monitoring, Toni blends signal analysis with field-based research to reveal how sounds are used to track presence, monitor populations, and decode ecological knowledge. As the creative mind behind Nuvtrox, Toni curates indexed communication datasets, sensor-based monitoring studies, and acoustic interpretations that revive the deep ecological ties between fauna, soundscapes, and conservation science. His work is a tribute to: The archived vocal diversity of Animal Communication Indexing The tracked movements of Applied Bioacoustics Tracking The ecological richness of Conservation Soundscapes The layered detection networks of Sensor-based Monitoring Whether you're a bioacoustic analyst, conservation researcher, or curious explorer of acoustic ecology, Toni invites you to explore the hidden signals of wildlife communication — one call, one sensor, one soundscape at a time.