The sounds of nature tell stories that science is only beginning to fully understand, and everyday citizens are now joining the quest to capture them.

From the gentle rustle of leaves in ancient forests to the haunting calls of nocturnal creatures, our planet produces an intricate acoustic tapestry that researchers call soundscapes. For decades, professional scientists worked alone to document these auditory environments, but a revolution is underway. Community science—where volunteers contribute observations and recordings to research projects—is dramatically expanding our ability to archive, analyze, and protect the symphony of nature that surrounds us.

This grassroots movement is democratizing environmental research in unprecedented ways. Armed with smartphones, portable recorders, and growing enthusiasm, citizen scientists are creating vast acoustic databases that would be impossible for traditional research teams to compile alone. The implications stretch far beyond simple documentation; these soundscape archives are becoming essential tools for conservation, biodiversity monitoring, and understanding how human activity impacts wildlife across the globe.

🎵 The Science Behind Soundscape Ecology

Soundscape ecology emerged as a distinct scientific discipline in the late 20th century, recognizing that acoustic environments contain valuable information about ecosystem health. Unlike traditional wildlife surveys that focus on visual observation, soundscape research captures the complete auditory profile of a location—including biological sounds from animals, geophysical sounds like wind and water, and anthropogenic noise from human activities.

Dr. Bernie Krause, a pioneering soundscape ecologist, documented how healthy ecosystems exhibit what he calls the “niche hypothesis.” Each species occupies its own acoustic frequency and temporal niche, creating a balanced sonic environment. When ecosystems become degraded, this acoustic organization breaks down—species disappear, and the soundscape becomes impoverished or dominated by human noise.

Professional researchers have traditionally used expensive equipment and spent months in the field to capture these acoustic signatures. However, the sheer scale of biodiversity loss and habitat change occurring globally means that conventional approaches cannot keep pace with the monitoring needed. This is where community science enters as a game-changing force.

From Birdwatchers to Bioacousticians: The Rise of Citizen Sound Recorders

The transition from casual nature listening to structured acoustic contribution has been facilitated by several technological and social developments. Smartphones with high-quality microphones, affordable recording equipment, and user-friendly apps have lowered the barriers to participation dramatically.

Projects like the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s extensive citizen science programs have shown that volunteers can collect scientifically valuable data when provided with proper training and protocols. What began with bird observation has expanded to encompass all manner of acoustic documentation—from insect choruses to marine mammal vocalizations.

The motivation driving these citizen scientists varies widely. Some are passionate nature enthusiasts seeking deeper engagement with their local environment. Others are educators using sound recording as a teaching tool. Many are concerned citizens who recognize that documentation is the first step toward conservation. Regardless of motivation, their collective contribution is enriching soundscape archives at an exponential rate.

Tools of the Trade: Technology Empowering Everyday Recordists 🎙️

The equipment used by community scientists ranges from professional-grade recording devices to smartphone apps designed specifically for nature sound capture. Mid-range portable recorders from manufacturers like Zoom and Tascam offer excellent audio quality at accessible price points, while smartphone apps provide instant participation opportunities.

Applications such as iNaturalist have expanded beyond visual documentation to include sound recording features, allowing users to upload bird songs, frog calls, and insect sounds alongside photographs. These recordings are timestamped, geotagged, and can be verified by experts within the community, ensuring data quality while maintaining accessibility.

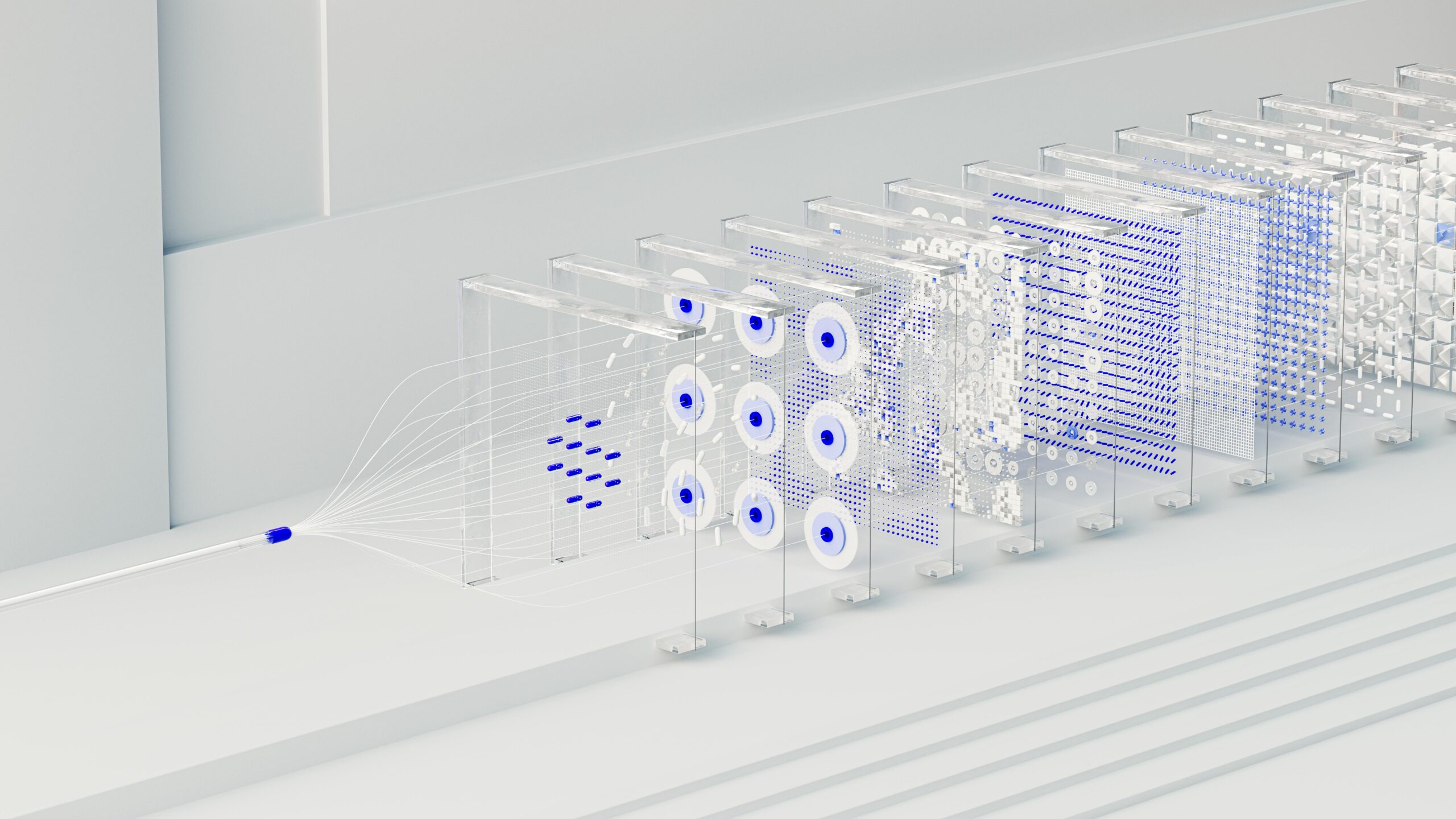

Other specialized platforms focus exclusively on acoustic data. Merlin Bird ID, also from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, uses artificial intelligence to identify bird species from audio recordings, simultaneously building a massive database of avian sounds while educating participants about the species in their area.

The key to these platforms’ success lies in their dual function: they provide immediate value to the user through species identification or community engagement while simultaneously contributing to larger scientific datasets. This reciprocal relationship sustains long-term participation and ensures continuous data flow into soundscape archives.

Quality Control: Ensuring Scientific Rigor in Crowdsourced Data

One legitimate concern about community science is data quality. How can researchers trust acoustic recordings made by untrained volunteers using varied equipment under inconsistent conditions? The answer lies in sophisticated verification systems and statistical approaches that account for uncertainty.

Many platforms employ multi-tiered verification processes. Initial automated filters check for basic quality criteria—appropriate file format, sufficient recording length, and adequate signal-to-noise ratio. Next, community verification allows experienced participants to review submissions, flagging those that require expert attention. Finally, trained scientists or AI algorithms make final determinations on uncertain identifications.

Research has shown that when proper protocols are followed, citizen scientist data quality can match or even exceed professional standards in certain contexts. The sheer volume of observations also allows for statistical treatments that can extract meaningful patterns even when individual data points contain errors. This robustness makes crowdsourced soundscape data increasingly valuable for serious scientific inquiry.

Biodiversity Monitoring Through Acoustic Signatures 🦜

One of the most powerful applications of community-collected soundscape data is biodiversity monitoring. Traditional biodiversity surveys are labor-intensive, expensive, and often limited in scope. Acoustic monitoring provides a complementary approach that can be scaled dramatically through citizen participation.

Birds, amphibians, and many insect species are particularly well-suited to acoustic monitoring because they produce distinctive vocalizations. A single recording session in a biodiverse location might capture dozens of species, each leaving its acoustic signature in the archive. When these recordings are collected consistently over time and across geographic areas, they reveal patterns of species distribution, population trends, and seasonal movements.

In tropical regions where visual biodiversity surveys are extremely challenging due to dense vegetation, acoustic monitoring offers a practical alternative. Community scientists living in or visiting these areas can contribute recordings that document species researchers might never otherwise encounter. This is especially valuable for nocturnal species, cryptic species that are difficult to observe, and rare or endangered species whose populations need monitoring.

Climate Change Documentation Through Sound

Soundscapes are proving to be sensitive indicators of climate change impacts. As temperatures shift, precipitation patterns change, and seasons become less predictable, the acoustic characteristics of ecosystems respond in measurable ways. Citizen scientists are documenting these changes, often without realizing the full significance of their contributions.

Phenological shifts—changes in the timing of biological events—are captured beautifully in soundscape archives. The first spring chorus of frogs, the arrival of migratory bird songs, and the emergence of singing insects all occur at specific times influenced by temperature and daylight cues. When thousands of community scientists record these events across broad geographic ranges over multiple years, the data reveals how climate change is altering these patterns.

In mountainous regions, acoustic monitoring by citizen scientists has documented species moving to higher elevations as lowland areas become too warm. In polar regions, community-collected recordings have captured the increasing presence of species expanding their ranges northward. These acoustic records provide compelling evidence of ecological change that complements temperature data and visual observations.

Urban Soundscapes: Documenting Nature in Cities 🏙️

While pristine wilderness areas capture the imagination, urban soundscapes represent crucial frontiers for community science. Cities are home to surprising biodiversity, and documenting the acoustic environment in urban settings reveals how wildlife adapts to human-dominated landscapes.

Citizen scientists in urban areas have documented fascinating phenomena: birds adjusting their song frequencies to avoid masking by traffic noise, species shifting their calling times to quieter periods of the day, and the acoustic signatures of urban green spaces that serve as refuges for nature in the city.

These urban soundscape archives serve multiple purposes. They help urban planners understand which green spaces are most valuable for biodiversity, inform noise mitigation strategies, and connect city residents with the nature that persists around them. Many urban participants report that contributing to soundscape projects heightened their awareness of nature in their daily environment, transforming their relationship with their city.

Marine and Aquatic Acoustic Archives

While terrestrial soundscapes have received the most attention, underwater acoustic environments are equally rich and increasingly accessible to community scientists. Specialized hydrophones—underwater microphones—have become more affordable, and coastal communities are contributing to marine soundscape archives that document fish vocalizations, marine mammal communications, and even the sounds of coral reefs.

Healthy coral reefs produce distinctive crackling and popping sounds created by snapping shrimp, fish, and other reef residents. These acoustic signatures correlate with reef health, making soundscape monitoring a valuable conservation tool. Citizen scientists in diving communities are contributing recordings that help researchers track reef degradation and recovery across wide geographic areas.

Freshwater environments also benefit from acoustic monitoring. Streams, rivers, and lakes each produce characteristic soundscapes influenced by water flow, substrate composition, and biological communities. Community scientists in watershed groups are creating acoustic archives that document baseline conditions and track changes resulting from development, climate impacts, or restoration efforts.

The Educational Dimension: Learning Through Listening 📚

Beyond data collection, community soundscape projects offer profound educational benefits. Participants develop listening skills, learn species identification, gain understanding of ecosystem relationships, and acquire technical skills in audio recording and analysis.

Schools have embraced soundscape projects as interdisciplinary learning opportunities. Students combine biology, technology, mathematics, and communication skills while contributing to authentic research. The tangible nature of sound recording—creating permanent documentation of a moment in nature—provides motivation and creates lasting records that students can revisit and share.

For adults, participation in soundscape citizen science often leads to deeper environmental awareness. Many participants report that focused listening transforms casual nature walks into rich sensory experiences. This heightened awareness frequently translates into conservation action, as people become advocates for protecting the soundscapes they’ve grown to appreciate.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite remarkable progress, community soundscape science faces ongoing challenges. Data storage and management present technical hurdles—audio files are large, and archives are growing exponentially. Processing and analyzing this data requires sophisticated automated systems, though artificial intelligence and machine learning are rapidly improving capabilities in species recognition and acoustic pattern detection.

Standardization remains an issue. Different projects use varying protocols, equipment, and metadata standards, making it difficult to combine datasets for large-scale analyses. Efforts are underway to establish best practices and interoperable systems that would allow seamless data sharing across platforms and research groups.

Equity and access represent important considerations. While technology has democratized participation to some degree, barriers remain for communities without reliable internet access, expensive equipment, or scientific literacy support. Expanding participation to underserved communities would not only increase data coverage in crucial areas but also ensure that soundscape science reflects diverse perspectives and values.

The Growing Archive: A Legacy for Future Generations 🌍

Perhaps the most profound contribution of community soundscape science is the archive itself—a growing library of acoustic snapshots documenting our planet’s biodiversity at this moment in history. As species decline, habitats transform, and climate continues changing, these recordings become increasingly precious.

Future researchers will mine these archives for insights we cannot yet anticipate. Patterns invisible in current analyses may emerge with new analytical techniques. Species we lose may be preserved acoustically, their songs available for study and perhaps even as templates for conservation efforts. The soundscapes of ecosystems we fail to protect will at least be remembered, their acoustic signatures preserved as reminders and warnings.

This archive also serves as a counterpoint to despair about environmental loss. It documents resilience, adaptation, and the persistence of nature even in challenging conditions. It celebrates the curiosity and dedication of thousands of individuals who chose to listen carefully and share what they heard. It represents hope that collective action can generate knowledge, build connections, and ultimately contribute to better stewardship of our acoustic commons.

Joining the Acoustic Revolution: How to Get Started

For anyone inspired to contribute to soundscape archives, getting started is remarkably straightforward. Begin with awareness—spend time listening to your local environment without recording, noticing the sounds that define different times of day, seasons, and weather conditions. This develops the focused listening skills that make recording sessions more productive.

Next, explore existing citizen science platforms to find projects aligned with your interests and location. Many provide training materials, community forums, and expert guidance. Start with simple recordings using whatever equipment you have available—smartphone audio quality is sufficient for many applications, and dedicated recording equipment can be acquired as your interest grows.

Consistency matters more than perfection. Regular recordings from the same location over time provide valuable temporal data. Geographic coverage is equally important—recordings from under-documented areas, whether remote wilderness or urban neighborhoods, fill crucial gaps in soundscape archives.

Finally, engage with the community. Share your recordings, participate in identification discussions, and learn from experienced contributors. The social dimension of citizen science sustains participation and accelerates learning while building networks of people who share appreciation for nature’s acoustic richness.

The symphony of nature plays continuously, whether we listen or not. Community science is ensuring that this symphony is not only heard but carefully documented, studied, and preserved. Every recording added to soundscape archives enriches our collective understanding of the living world and strengthens our capacity to protect it. In an era of profound environmental change, these acoustic snapshots created by engaged citizens represent both scientific resource and cultural treasure—a testament to curiosity, dedication, and the enduring power of simply paying attention to the sounds that surround us.

Toni Santos is a bioacoustic researcher and conservation technologist specializing in the study of animal communication systems, acoustic monitoring infrastructures, and the sonic landscapes embedded in natural ecosystems. Through an interdisciplinary and sensor-focused lens, Toni investigates how wildlife encodes behavior, territory, and survival into the acoustic world — across species, habitats, and conservation challenges. His work is grounded in a fascination with animals not only as lifeforms, but as carriers of acoustic meaning. From endangered vocalizations to soundscape ecology and bioacoustic signal patterns, Toni uncovers the technological and analytical tools through which researchers preserve their understanding of the acoustic unknown. With a background in applied bioacoustics and conservation monitoring, Toni blends signal analysis with field-based research to reveal how sounds are used to track presence, monitor populations, and decode ecological knowledge. As the creative mind behind Nuvtrox, Toni curates indexed communication datasets, sensor-based monitoring studies, and acoustic interpretations that revive the deep ecological ties between fauna, soundscapes, and conservation science. His work is a tribute to: The archived vocal diversity of Animal Communication Indexing The tracked movements of Applied Bioacoustics Tracking The ecological richness of Conservation Soundscapes The layered detection networks of Sensor-based Monitoring Whether you're a bioacoustic analyst, conservation researcher, or curious explorer of acoustic ecology, Toni invites you to explore the hidden signals of wildlife communication — one call, one sensor, one soundscape at a time.